Nothing says the holiday’s like stabbing someone with a toy.

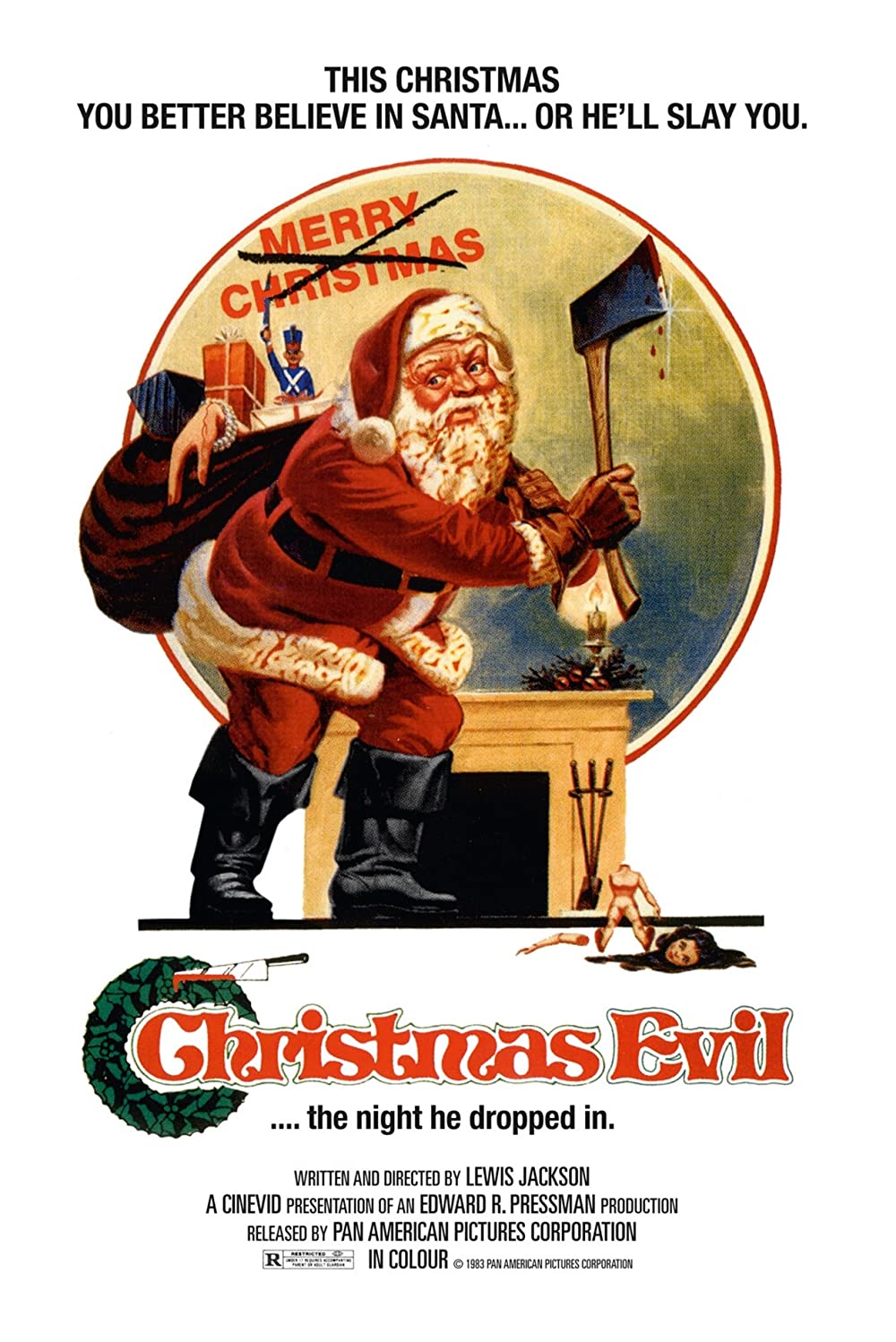

Joined by special guest Sarah Currie, this Christmas season we turn our attention to cult classic holiday slasher film, Christmas Evil. But will this typical “mentally ill people are dangerous” romp exceed expectations? Probably not, but at least we got the present we all wanted this year — an answer to the age old question of what happens when a son sees mommy kissing Santa Claus.

Listen at…

Grading the Film

As always, this film is reviewed with scores recorded in four main categories, with 1 being the best and 5 being the worst. Like the game of golf, the lower the score the better.

How accurate is the representation?

Jeff – 4 / 5

Erika – 2.5 / 5

Sarah – 4 / 5

Total – 10.5 / 15

How difficult was it to watch the movie?

Erika – 4 / 5

Jeff – 1 / 5

Sarah – 3 / 5

Total – 8 / 15

How often were things unintentionally funny?

Erika – 5 / 5

Jeff – 3 / 5

Sarah – 5 / 5

Total – 13 / 15

How far back has it put disabled people?

Jeff – 4 / 5

Erika – 4 / 5

Sarah – 2.5 / 5

Total – 10.5 / 15

The Verdict

Crimes Have Been Committed *

Podcast Transcript

Erika:

Welcome to Invalid Culture, a podcast dedicated to excavating the strangest and most baffling representations of disability in popular culture. Unlike other podcasts that review of films you’ve probably heard of, Invalid Culture is all about the abyss of pop culture-adjacent media that just never quite broke through because, well, they’re just awful. I’m your host, Erika.

Jeff:

And I’m your other host, Jeff, and it’s time now for us to think about some culture that might just be invalid.

[Theme song plays, “Arguing with Strangers on the Internet” by Mvll Crimes]

Erika:

Welcome back to another episode of Invalid Culture. It’s that time of year y’all, Chrismukkah is upon us, and that means it’s time for our festive holiday special. Jeff, how you doing?

Jeff:

So hype, very excite. I’m really looking forward… Not that last year’s Christmas episode was any slouch, it’s not every day you get to interview a literal movie star on your podcast. But, no shade to Hallmark, this was a much more heartwarming Christmas tale in my opinion.

Erika:

Huh.

Jeff:

A silence, complete silence.

Erika:

Heartwarming is not how I would’ve described this film, unless you are maybe making a reference to the torch mob?

Jeff:

Yeah, we’re different people, Erika, I think that should be very clear.

Erika:

I do forget that sometimes.

Jeff:

We’re not just different people, we also, as always, this season, have a different person with us. Today we are joined by our guest victim, Sarah. Sarah, can you give an introduction for our fair listeners?

Sarah:

Sure. My name is Sarah, and I professionally do nothing for a living. I am finishing up my doctorate in disability, and I teach classes, and I watch a lot of movies and pretend that that’s an important service to society.

Jeff:

As a media scholar, I can confirm it is.

Sarah:

Naturally.

Erika:

It sounds like you are in the right place.

Sarah:

Yeah. There is no bias here whatsoever as to the veracity of my job.

Jeff:

What would some of our listeners know you from, published work, or studies, or anything? Movies?

Sarah:

Movies! The long list of films that I have appeared in!

Jeff:

Yeah.

Sarah:

You may know me from rants that sound slightly detached from reality on Twitter, or sharing resources online, or publications about UDL in such fantastic venues as criticism, literature, Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics, Mosaic.

Jeff:

That’s it. But no feature films.

Sarah:

But no feature films, no. I actually turned down the Deadpool movie that’s coming out next year, because I’d really like to do my dissertation defense.

Jeff:

Right. Priorities, right?

Sarah:

Yeah.

Jeff:

All right, so Erika, I think you need to tell us what monstrosity did we have to endure this year?

Erika:

This year, the gift that just keeps on giving is Christmas Evil. Christmas Evil brings us the vivid tale of the life of Harry Stadling, a man traumatized as a child by the sight of his mother getting frisky with St. Nick. Making Freud proud, this traumatic event leads to a lifelong obsession with Santa Claus and all things Christmas, until, 30 years after the trauma, the lines between Harry and Santa begin to blur. Troubles at the toy factory he works at, and the negative body hygiene of local bad boy Moss Garcia, eventually push Harry over the edge. Those who stand against the Christmas will die. Dressed as Santa, Harry goes on a part donating toys to disabled kids, part murder rampage to punish those who don’t want to hear the, quote, “tune he’s trying to play”, end quote. Whatever that means. Eventually, he confronts his financially successful repo man brother Philip, for denying his traumatic observations, and after tussling for a bit and eventually punching Philip, Harry loads up into his Santa van, flying off into the cold night to escape the torch-wielding mob that is hunting for him.

Sarah:

That’s actually a better summation than actually subjecting yourself to the film. That did a lot of work, rhetorically, to save people a lot of time and trauma.

Jeff:

That’s about a hundred minutes condensed into a tight paragraph.

Sarah:

I’d like to draw attention to the fact that the first 45 minutes of this film was actually expository content to a plot line that basically didn’t exist.

Jeff:

Right, yes, a hundred percent. A hundred percent.

Erika:

It was like, “We’re just putting in the time before we can start killing people.”

Sarah:

Yeah. It took a really Tolkienesque approach to what was a film that was fairly devoid of any context whatsoever. It took me 20 minutes into the film to figure out that his Peeping Tom house was his brother’s house, because there were so many balding, middle-aged, brunette males in the film, I had trouble keeping track. Every single male cast fit that description, and it made it really hard.

Jeff:

Is this why I like the film so much? Am I drawn to the balding, brunette male demographic?

Sarah:

Which character did you relate the most to?

Jeff:

Obviously Moss Garcia.

Sarah:

Moss Garcia.

Jeff:

Moss!

Erika:

That’s the child that asked for a subscription to Penthouse or Playboy?

Sarah:

Penthouse magazine.

Jeff:

Yeah, yep. Now, we are already cutting into this and joking around, but our opinions don’t matter, because there are legitimate scholars who have weighed in on the quality of this film, and we think it’s important for us to give fair shake to that critical response to this film. There wasn’t a lot of critical response, because it’s actually kind of hard to get your hands on this film back in the 1980s. However, one Tom Huddleston, wrote on Time Out, gave the film a four out of five, and most importantly gave us this great quote. So Tom Huddleston says, quote, “In contrast to most slasher flicks, this isn’t about anything as simple as revenge. Jackson’s concerns are bigger; social responsibility, personal morality, and the gaping gulf between society’s stated aims at Christmastime: charity, hope, goodwill to all men; and the plight of those left on the outside: the children, the mentally ill, the ones who don’t fit in. Bizarre, fascinating, thoughtful, and well worth a look.” These are the words of Tom Huddleston. Of those adjectives, Sarah, how many of them were accurate to you?

Sarah:

There were four, I guess. I would go oh for four. The closest he gets is maybe “well worth a look”, but it kind of has the same ethos as rubber necking for me, where you look at the car accident and you know shouldn’t be looking, but you also can’t look away because now you’ve already seen it, so you feel invested. That was my relationship to Christmas Evil.

Jeff:

Yeah. What about you, Erika?

Erika:

I guess I was watching it and there’s, we’ll get there, but there’s a strong kind of anti-capitalist vibe in the film that I think just turned me a little more compassionate towards it. I was like, “Okay, you’re kind of speaking my language here. Tell me more. This is weird, but I’ll keep listening.” And so maybe Tom was coming from a similar place.

Jeff:

Right, yeah. I came for the disability narrative, I stayed for the strong union rhetoric.

Erika:

Yes.

Sarah:

It’s true. The unionization undertone that outplayed the entire film was actually more resonant than the core storyline, which I’m not sure is what they were going for, but that’s what they got.

Jeff:

Tom wasn’t the only one though who enjoyed this film. In fact, there are some pretty famous people, like John Waters, who have stated that this is maybe the best Christmas movie he has ever seen…

Sarah:

What?

Jeff:

Which is a nuclear hot take. But people on Amazon also have some affinity for this film. Specifically, we have our user Earl Awesome, pretty sure that’s his real name, gave this a five star, with the title Best Christmas movie ever, period, ever, all caps. Two evers. This is what Earl had to say about the film. “I was hesitant to order this, but when I read a statement from John Waters, if you don’t know him, you should, saying it was the best Christmas movie ever. He was right. What’s more, is that this movie is where the idea for,” quote, “Joker came from. Everything in Hollywood is copied. You watch the protagonist descend into madness as the holiday season approaches. It’s an all too real comment on the way holidays can play with the mental health of some. Great acting, great story, great movie, five stars.”

So, I just want to contest, right off the bat, that the Joker existed decades before this film was ever made, so this is definitely not where the idea for the Joker comes from, in any way. I think there’s probably a few other movies like Taxi Driver that also would like to have a word on that. But the question I have for you, Sarah, would you say that this movie was a comment on the way that holidays can play with the mental health of some?

Sarah:

I know where he’s coming from with this, because while I was watching this, and this is kind of a reductive comment, but Harry, our protagonist, our possibly actually real Santa Claus, depending on how you read the ending, is kind of a confusing potpourri of mental illnesses and symptoms that don’t ever really congeal into one credible diagnosis, and I thought the reference to the Joker was really good because at least Christopher Nolan’s version… That is also a character that’s kind of a confusing mass of symptomology that doesn’t actually cohere with anyone’s real, lived experience of psychosis. So I appreciated that somebody had read a comic book at some point and identified like, “Okay, here are some core mental illness symptoms.” They just didn’t care too much for the cohesion of those symptoms into something resembling a diagnostic disorder. And you can argue about whether somebody needs to meet the criteria of a diagnostic disorder to be a credible mentally ill protagonist.

But all that to say, I don’t know if it actually even takes on mental health problems at Christmas, because it just kind of takes on the problem of being completely unable to identify how mental health interacts with a person in general. So if you can’t even get into the person’s psyche, I don’t know how you’re going to then translate it to the level of your psyche’s interaction with a holiday. Right? Does that make sense?

Erika:

That’s actually a surprisingly reasonable segue into our next review, which-

Sarah:

Thank you.

Erika:

… comes-

Sarah:

I thought you were going to say a surprisingly reasonable answer, and I’d be like, “Thank you. I’m here to defy expectations.”

Erika:

“Glad you set the bar so low.” Yeah, so megalon, maybe also dealing with some low standards, gave this a five-star review, titled Fantastic, in which they wrote, “Quite possibly the greatest movie about a man obsessed with Christmas ever made. The depiction of psychosis is frighteningly real, and yet there are moments of hilarity and shocking violence. Highly recommend,” three exclamation points.

Sarah:

Okay.

Erika:

My first question is what about Elf?

Sarah:

That is actually, arguably, a better depiction of psychosis than Christmas Evil.

Erika:

Yeah, that was going for a man obsessed with Christmas, but totally. And what about this depiction of psychosis was…

Jeff:

Frighteningly real.

Erika:

Real or frightening?

Sarah:

If we again return to the metaphor of somebody read a comic book that lightly referenced a villain with mental illness, and then they modeled their character with psychosis after that? Yes, that would be frighteningly realistic, and incredibly expository as to the hyperbolic mentally ill villain who cannot be understood, and every action he takes is both confusing and incredibly tragic. Is that the lived experience of psychosis, in my mind and my community’s mind? I think it would be an emphatic no from everyone in the room.

Jeff:

Our last review comes from, again, I’m pretty sure this is their real name, Davy Dissonance. Davy gave this a two-star, with the title, “The picture quality is watchable and audio is good. Movie Review”. Yeah, I’m going to try my absolute best to not laugh during this, so I’m going to try and do Davy justice here. Davy did not love the film. Okay. Davy says, “As everyone else pointed out, it’s not a slasher movie. It is a demented Christmas movie, pretty much. There are moments when Santa kills, but it’s one home invasion and mass slaughter. That’s it. Anything else is Santa having a period about the fact that no one gives a shit about Christmas or whatever. I didn’t hate this movie. I don’t regret ever watching this, but it’s not my thing. It’s innovative and different, but for some reason I do not give one F about it. I found the movie boring. So up yours.”

Erika:

Wow.

Jeff:

Is Davy Dissonance Harry?

Sarah:

Is Harry Santa Claus?

Jeff:

Well, okay, so that’s maybe a better place for us to start. Number one, does Davy not realize that there is a difference between Harry and Santa?

Sarah:

I don’t know if I understand whether there is a difference between Harry and Santa Claus. The last 45 seconds of that film? I was up for an extra hour last night just laying there, thinking about it. Does that mean…

Jeff:

[inaudible 00:16:42] give me more?

Sarah:

Was he Santa the whole time? Is the joke on the viewer? That we were making fun of this guy, but that guy has actually been the real Santa for the entirety of this film? And all that context building for the first 45 minutes is actually irrelevant?

Jeff:

Yeah, that’s an important question.

Erika:

I have another important question. Is Davy, I haven’t heard this phrasing before, but when Davy asks, “Is Santa having a period?” About the fact that no one gives a shit, is “having a period” slang for being crazy or having an episode?

Jeff:

So I had this question as well, as someone who did not get sex education, I don’t also understand how periods work. And so I also was curious about this. Do you just have a period? Do you bring it on? Is it triggered by things?

Sarah:

That is a mid-millennial slang for PMSing about something.

Erika:

Are we early millennials? Is that what happened here?

Sarah:

I’m not saying that that’s what happened, but I might be strongly implying that that’s what happened.

Jeff:

But still a confusing one to me, given my limited knowledge of how female anatomy works.

Sarah:

A hundred percent. I think that Davy Dissonance can be accused of some anti-feminist rhetoric if we subscribe to third or fourth-wave feminism, and Amazon did not do a good enough job curating that review for use of language that could be offensive to 50% of the population.

Erika:

How did they miss “up yours”?

Jeff:

From now on, I’m just going to put this out there though, every time I now write a review about a movie, and possibly academic books, I’m ending it with, “So up yours.”

Sarah:

If you don’t agree with this, up yours.

Erika:

I might argue that academic writing is just very, very fancy and creative ways of saying “up yours” without saying it.

Sarah:

It’s true. Davy went the extra step of saying the quiet part out loud, and I appreciate him for it.

Erika:

Props for that.

All right, so we’ve heard what the critics had to say, but let’s just take a step back. General impressions of this film. What did you guys think?

Sarah:

I had a lot of trouble with the light pedophilia vibe that permeated this entire film. It made me deeply uncomfortable, and it really does nothing to address it. It normalizes it to such an extent that you would find it weird if this film was your only context for ’80s New York men, if they weren’t into little girls and had pictures of them on their nightstands and shit. Which I thought, for a number of reasons, was just weird.

I did really like how much content there was on the Willowy Springs Hospital for mentally retarded children, and that was the words they used, not the words I’m using. I wrote down, this is my headcanon, the real villain in this movie is intense social anxiety. This is really about Harry’s journey with not wanting to be in spaces with other people or talking to others, and everything else is just a byproduct.

Jeff:

Would you say that this was a frighteningly real portrayal of social anxiety?

Sarah:

I think especially the scene where he goes, this is about halfway through the movie, where he goes to the Christmas party and they drag him in against his will, and then he’s standing and everyone’s staring at him and he starts assuming that they’re going to start shit-talking him. I was like, “That’s actually a pretty good depiction of how social anxiety works in real life.” And I do not think they were going for that at all, but it ended up being a fairly accurate depiction of a kind of medically treatable variant of anxiety. That was laudable in this film.

Erika:

So that actually dovetails really well with my read on the film. For me, this quickly just morphed into a trauma narrative. It’s obviously set up to be that, but it kind of set me off on this contemplation about trauma, and generational trauma, and the role of trauma in mental health. That was really what I spent, I think, the greater part of this movie thinking about. The pedophilia question came up for me too, so we’re going to have to spend a little time with that. It was indeed difficult, very difficult to get through this film. I’m not a horror film… That’s not my genre, but yeah. The Willowbrook bit too, really, that kind of threw me. I guess that pulled me in too, because it was like, “Wait a sec, why? Whoa, whoa.” What in the creation of this film led to that becoming part of the story? To the point that they found a Geraldo lookalike to be the newscaster. That was curious to me.

Sarah:

Yeah.

Jeff:

Yeah. When we picked this film originally, we hadn’t seen it yet, and I think going into it, I thought we were going to get this sort of typical, kind of schlocky like, “Ooh, crazy man goes on a rampage.” And I’m not saying we didn’t get that, but we also got a lot of other confusing things as well that I was not expecting. And I now, in my head, just constantly hear, “Moss… Moss…”

Sarah:

“Moss Garcia!”

Jeff:

“Moss Garcia!” In my head, and I’m going to put that in the positive category. I also want to see Moss Garcia get what’s coming to him as the original bad boy, the original bad boy of New York. And that young Moss Garcia would eventually become Rudy Giuliani.

Sarah:

But in this timeline, Harry is actually older, and Harry might be the original original bad boy, A, if he’s Santa, because that means he’s immortal. So that puts his age as ageless. But B, because the characterization of him is ostensibly a middle-aged man with a burn book and a Santa kink.

Jeff:

Right, basically, yes.

Sarah:

That’s pretty bad!

Jeff:

Yeah. Yeah. Anti-hero, some might say

Sarah:

“It’s me, I’m the problem, it’s me.”

Jeff:

Okay, so we’ve talked a little bit about the high-level stuff, but, I’m sorry, can we please talk about the inciting incident? This movie begins with a scene in which two young boys are witnessing Santa come down, wash his hands in a hand-washing station, as, apparently, you’re supposed to do for Santa. I did not do that in our household. He then butters himself some bread, which I also think is pretty off-myth. He drinks some milk, and everything’s great. But unfortunately, young Harry comes down and watches Santa moan very suggestively to his mother while taking off her garter belt, and then presumably consummated the relationship. Presumably. Harry then goes upstairs, he drops his snow globe, and cuts his hand on it.

Sarah:

I really thought they were going to do more, and I’m not condoning this, but I thought they were going to do more with the self-harm narrative as the inciting incident for violence. I thought it was going to be a kind of The Machinist thing, where wherever he sees blood, or the instantiation of food or eating, he goes into this kind of inarticulate psychosis and begins murdering people. They did that once, and then dropped that whole concept from the rest of the film, which I thought was kind of unfortunate because it was a somewhat interesting way to do it, but still problematic. It’s worth pointing out that that’s not how psychosis works in real life. There are such things as triggers, but if they have a self-harm trigger, it does not compel psychotic individuals to activate incredible violence upon the viewing of blood, or any such alternate instantiation. And I think that’s worth pointing out.

Erika:

I’m just remembering him now. The fact that Santa’s costume was perpetually covered in blood, I hadn’t really thought about that, the blood. Yeah, that wasn’t what stuck with me. First of all, I just was very confused. So, the boys think it’s Dad being Santa?

Jeff:

[inaudible 00:26:51] Philip does, Philip believes it’s the father, and Harry believes it’s actually Santa.

Sarah:

That’s actually their core, that’s what drives the ethos of the film, this disagreement that separates two brothers, but also, apparently, completely separates mental states between the two brothers.

Erika:

But I remain confused.

Sarah:

Yes.

Erika:

Was it his dad? Was it their dad? I don’t know.

Jeff:

According to the box, it was his father. The description of the film says he witnessed his father dressed as Santa. Now, I’m not a psychologist or a psychiatrist, but I want to dig into this Oedipal complex a little bit more. So, he has this desire for his mother, and Santa, I guess, gets his mother. And so then he becomes obsessed with Christmas 33 years later? Because when we see him next as an adult, his house is like Santa’s workshop. It is decked out. He has a chalkboard counting down the days to Christmas, he has every toy, everything. And then of course his proximity to Santa becomes more and more evident as it goes on. But I’m just curious about what Freud would think about this. He sees his mom, and then is like, “I will become Santa.”

Sarah:

I hate Freud. That’s my bias. I think his theories are fucking useless. I think a better reading than Freud would give, but maybe Freud would be sympathetic too, would be something like Harry is enlivened by the sexual potentiality of specifically Christmas, and begins to associate any kind of sexual action with the prospect of Christmas Eve, without really taking too much time to think it’s possible his parents have also done these actions at other points of the year, and becomes so sexually fascinated by the relationship between Christmas Eve and the lewd acts performed, that he’s just caught in this continuous loop of Christmas, sex, mother, sexiness, Santa, in this recurring spiral of illness?

Jeff:

Which admittedly sounds like a nightmare, if I put myself into that situation of 33 years of weird sexual Christmas tension.

Sarah:

Yes.

Jeff:

Nightmare.

Sarah:

Absolutely.

Jeff:

Yeah, yeah. I also wonder though, why has no one said anything about this to him?

Sarah:

There’s kind of the implication at the end of the movie that this is a somewhat regular argument between the brothers, Phil and Harry, when they’re having their kind of penultimate argument before the punching scene. And he’s like, “You’ve ruined my life. We can’t keep doing this kind of thing.” And calling back to all these occasions where they’ve argued over whether Santa’s their dad, and that inciting incident in the ’30s. And because of this incident, I think instead of causing Harry to question his drawn relationship between repressed sexuality and Christmas Eve or Christmas, it reinforced it for him, right? Kind of the same way if you tell a child you can’t have the Kit Kat bar, they become obsessed with wanting the Kit Kat bar. You don’t even have to like Kit Kat; if I tell you you can’t have it? That’s all you want at this point, even if just to spite me. And that’s a very Freudian reading of our desires, and how desire mechanics work in a psyche. But he seems to be enacting that in his relationship to smut and Christmastime.

Erika:

Yeah, I don’t know if it’s necessarily like… Definitely the film communicates the Oedipal vibe is there, but I think another read of it is not necessarily sexual in that way. That he’s so upset at seeing Santa do what Santa… Santa’s supposed to be innocent, and I think he goes on this life mission of recuperating Santa’s innocence. That, “Santa did it wrong, I’m going to fix this. I’m the real Santa, I’m going to fix this. I’m going to…” And that also kind of wraps in the… He’s obviously upset about the Moss… Moss’s sexuality.

Sarah:

Moss Garcia!

Jeff:

Moss Garcia!

Sarah:

You can’t just say it normally, you have to say it like he says it. Moss Garcia!

Erika:

It’s just like sex isn’t part of Christmas, sex is bad, it is not part of Christmas. And so this kind of brings up that pedophilia question, because I think pedophilia is one read of it, but the other read of it is there’s something paternal, and there’s also something infantile about his relationship, or he’s grasping onto this kind of childhood innocence.

Sarah:

Which is, notably, a trait that many people associate with mental illness.

Erika:

Yes.

Sarah:

Often erroneously. I think he was intentionally written to be childlike, and almost kind of nymphlike, and you laugh at his attempts at interacting with adult society because he’s just so infantile and innocent.

Erika:

But the fact that the pedophilia comes out, it’s almost like they didn’t commit to that. They didn’t commit to us feeling innocence about his sexual conversation with children.

Sarah:

So if he thinks Santa did it wrong, is Santa doing it right for Harry doing it with much younger girls?

Jeff:

An interesting query.

Sarah:

That’s a big yikes from me for Harry.

Jeff:

Fair enough.

Sarah:

The first thing he says to one of the girls in the alley when he meets up with them, he says some inane comment to Moss Garcia, but then to the girl in the group, he goes, “You’re very beautiful.” And I was visibly cringing at that line when he says it.

Jeff:

Yeah. Well, he does the same when he sort of strokes the picture, right?

Sarah:

Yeah.

Jeff:

He’s like, “Oh, beautiful.”

Erika:

Great. Real quick, why does he have a picture of the child?

Jeff:

How did he get this photo?

Sarah:

And it seems to be a school photo.

Erika:

Yeah.

Sarah:

He got that from someone.

Erika:

It sort of gives the impression, when I saw the school photo, I was like, “Did her parents give him that?” Is that part of how he’s perceived by others, is as this mentally ill or disabled older man, who the neighborhood is kind of like, “Oh, we accept him. He’s just the weirdo.”

Sarah:

That was definitely the function of Philip’s wife. Philip’s wife was-

Erika:

Oh my gosh.

Sarah:

… Team Harry the entire film. And I actually loved it, because she comes downstairs and uses her sexuality, which I think is an important element that they did entirely unintentionally, to convince people that Harry is worthy of people’s time. So it was this reversal of the sexuality mechanic that’s working on a higher level in the film, which again, unintentionally, I think they were using in reverse, to try to enforce the message, “I don’t think you should see this guy as some dipshit child. I think he is a man who has struggles like you do, and is worthy of the attention that you give to me or the other people at work.”

Erika:

I think we also need to talk about the office party, and this whole Willow Springs, Willowbrook coming up, because we’re talking about who he is and how people perceive him, but he’s in a management position at work, isn’t he?

Sarah:

Yes.

Jeff:

Yeah, he just got promoted to management.

Erika:

But there’s some dynamic there where he’s sort of being branded as a sucker, right? Because someone’s calling him and asking him to, even though he’s been promoted, can you go and do the lower level work?

Sarah:

Yes.

Jeff:

Yeah, he’s referred to as a schmuck on more than one occasion.

Erika:

Okay. So we’re at this office party, Christmas party, everybody’s having a great time. Looks like typical ’80s office party, as I can imagine, office parties were typical in the ’80s. Why is the Geraldo expose coming up on the TV then and there?

Jeff:

[inaudible 00:36:49], so I have some theories on this. So I think that there’s a practical thing going on here in the film. And then I think there’s actually a more interesting thing that I want to actually talk about. So I think on the very legitimate, practical thing, is that I think they’re trying to point back to things like A Christmas Carol, the idea that Christmas is when you take care of disabled children. And so they were like, “Okay, well, we need to have these disabled children, and that he finds out that the corporation has said they’re going to help, but they actually aren’t.”

And this is where the interesting union politics happen, because as it comes out, they have this announcement, that for every toy that’s made, they’ll then donate a toy to this hospital, right? And Harry comes in and is like, “Wow, we have enough, how many children are there?” And the PR and exec guy was like, “Who cares? We’re never going to do it!” Basically. He’s like, “I don’t need to know how many children there are.” And so I’m like, “Hm, interesting that this is about generating productivity through a charitable appeal.” They’re like, “We need you to make more toys, so we’re going to bait you with this idea that your extra labor will help sick kids.” Whether or not that’s actually true, which Harry finds out it isn’t, and that’s kind of what triggers one of his reasons for killing.

But the fact that they would point back to Willowbrook, the institution in New York that famously Geraldo blew up in 1972 as being a horrendous, horrendous place for people with intellectual disabilities and other diagnoses. They use this, they intersplice clips from that actual documentary with their fake Geraldo, which I’m guessing it’s because that character returns later in the film, so they needed to situate them in the world. But it’s interesting that there’s this pointing to a really significant moment in disability rights history in the United States, rooted in the brutality of institutionalization, but then it’s being leveraged purely as this emotional appeal justification for why he’s going to go off, because of this unexcusable injustice that these children aren’t being given toys. When the actual injustice pointed out by this documentary is nothing to do with toys, and everything to do with state structural problems. But I think probably everyone in New York would know. Everyone knew Willowbrook, especially in 1980.

Sarah:

Okay, can I get you to pause there, because you have delivered an entire essay in the last three minutes, and I’m overwhelmed with things to say. So before you do essay number two…

Jeff:

Yeah, I [inaudible 00:39:54] agree.

Sarah:

I’d like to respond to essay number one.

Jeff:

Right.

Sarah:

Yeah. I think there was a lot going on with the institutionalization scene, and one of the most complicated parts of it was that 90% of that argument, which you so beautifully articulated, was implied, right? There was no dialogue about that whatsoever. You were supposed to see those scenes, and it was like a 9/11 for us in the present day, where there’s about 30 articles that are generated for you upon seeing this, and you don’t get any of that if you are not from an American context, or you have never heard of this incident, or you have not done any reading on institutionalization. So that’s already incredibly complicated.

And I think his relationship specifically to it has a couple competing layers of complications, some of which you’ve pointed out. But Erika did a great job of pointing out that it’s not actually so easy to posit him as this childish learning-disabled character because A, we go back to the potpourri of senseless symptoms that make it really hard to even investigate what he was trying to depict. But B, he is actually really good with children, and they go out of their way to show you that at the Christmas party, that when you get him out of his shell of social anxiety, he is actually brilliant with children, and should not be middle management at a factory, he should have a child-facing job, because he has talents and abilities that are extremely applicable to that.

So you get the narrative about being strung along or pushed into a career choice that people are told are more worthy employment, or more normal employment, and normal’s being used carefully there. But you also get this storyline about maybe it’s not that he is entirely infantile or more relatable to kids, maybe he has a genuine talent with kids, because if Harry was coded as female and had a lot of those traits, we would say, “Oh, she should have been a teacher. She should have been in ECE. She should have been all of these child-facing roles that are often coded as feminine.” And because Harry is a creepy looking, mask presenting guy, we see that, and they complicate this with the pedophilia storyline, we see that as creepy when he’s really good with kids, when he’s a great Santa Claus.

I thought when he was repeating that line like, “Merry Christmas to everyone!” Over and over again, that was a reference to It’s a Wonderful Life? I thought that they were trying to bring that back over and over again, and that has an interesting relationship to the institutionalization storyline, because that film is about, basically, ADA laws, right?

Jeff:

Yeah.

Sarah:

So I thought that that was intentional, where they were doing It’s a Wonderful Life, and they were doing some of the law rhetorics around institutionalizing kids. But then when you brought up, which movie did you say? Could be that one too.

Jeff:

Oh, A Christmas Carol. A Christmas Carol.

Sarah:

A Christmas Carol, yes. But I thought It’s a Wonderful Life specifically because of the legal context.

Jeff:

Yeah, totally. When he arrives at Willowy Springs, I thought for sure we were going to go in, and that he was going to have another moment of realization, another breaking of innocence. I thought that’s where this was going. He had the breaking of innocence with his dad, possibly Santa, and his mom. And then he has the breaking of innocence when he finds out that the corporation is not actually donating toys like they say they are. And then he was going to have this breaking of innocence that the institutions were not all happy places for children. I thought that’s where this was going. But then he just drops off the presents, gets kissed by a nurse, and then [inaudible 00:44:02] off into the darkness.

Sarah:

Counterpoint, I actually loved this. That scene for me was one of the stronger ones in the film, because of what he says to the security guard. So he rolls up as Santa Claus, we’re not sure if he’s actually real Santa or not, but whatever. And he goes, “Okay, I’ve got gifts for children.” And the guy brings up the same bureaucratic rhetoric that stops the toys from being donated in the first place. He says something to the effect of, “Oh, it’s so late at night, you can’t give kids toys now.” And his rebuttal is like, “What a ridiculous argument. Why can’t I donate toys to needy children because it’s past due hours? Just let me drop them off.”

And it was a really nice callback, actually, to his argument at the Christmas party where he’s using that really stupid tune metaphor. But I think it was trying to accomplish something along the lines of, “Everyone here is kind of out for themselves, and only doing something insofar as it helps them climb the ladder, and I don’t understand why no one else wants to help other people climb the ladder.” So the security guard for him is just another instantiation of all the dipshits at his work, and his boss, and all these people who won’t donate, won’t work in community, come up with stupid bureaucratic reasons to not do things. And he’s standing there like, “I am literally the image of charity right now. I am literally Santa holding gifts, and you’re not letting me do this, because it’s after hours. That is bonkers.”

Erika:

After hours, which is literally when Santa comes.

Sarah:

That’s true, yeah!

Erika:

But also, I’m curious, do you think if the security guard hadn’t let him in, would he have killed the security guard?

Sarah:

Definitely. I thought that’s exactly where that was going. I thought he was going to start slaughtering anyone who was too into the bureaucratic method. And that would’ve actually made me love the movie more, if he just went around eliminating people who were too hyper-capitalist.

Jeff:

Bureaucrats, like middle management specifically, is his target.

Sarah:

Yeah. If that was, from the beginning, his intentional targets, and it kept a somewhat coherent mission of just eliminating people who would’ve been the villains in It’s a Wonderful Life, it would’ve been a pretty good social commentary film.

Erika:

But there was also the way that the institution staff were the happiest, most wonderful, gleeful people in the universe.

Sarah:

Oh yeah.

Erika:

They’re overflowing. It was like, “Wow, that’s…” One read of it anyway is along that charity trope, that these must be the absolute salt of the earth humans that are in this wretched place with these others.

Sarah:

Yeah.

Jeff:

Yeah. And that’s this disconnect where it’s like they point to an awareness of what was going on at Willowbrook, the actual Willowbrook, but then also present this completely other world at the Willowy Springs that he actually attends.

Sarah:

Yeah. In fairness to people who actually do take on roles at psychiatric institutions, my bias here is my best friend is a nurse at an adult psychiatric institution. Some of them really are salt of the earth, better than average people. She is doing some incredibly difficult work there, and her job is legitimately beyond most people’s ability, and I really want to acknowledge that. That said, it is complete propagandistic nonsense that every single nurse and staff member that works there is the salt of the earth, my best friend, type employee, particularly in the ’80s, when the core de-institutionalization movement is happening in the US/Canada.

Jeff:

And on Christmas Eve.

Sarah:

And on Christmas Eve.

Jeff:

I think you are not going to find too many people getting paid what we pay support workers happy on Christmas Eve at work, probably.

Sarah:

Yes. There’s a lot happening there with those nurse characters.

Jeff:

Yeah. And then my last question on this one is, is this the moment when the sexy Santa myth is confirmed for him? Because this is the only instance where he, quote, unquote, “gets the girl”. This is the only moment where a woman looks at him with sort of loving eyes, and kisses him, and he lights up as well. Is this sort of the confirmation? And then what does it mean that the confirmation, the sexual confirmation, comes from a nurse, who are typically seen in this maternal kind of way?

Sarah:

I love this reading. I did not think about this at all, because I was too busy dwelling over the myriad institutionalization rhetorics from my own bias. I think, first impression, completely ad hoc, it kind of competes with the sexualization storyline that was already occurring, because that storyline was created to be so deeply problematic. And that’s not to say this is a non-problematic relationship and therefore those things don’t cohere, because it is A, also problematic. And B, problematic things can absolutely cohere.

But having been rewarded for standing up against bureaucracy, I think was, in the basest way, a positive way of rewarding his behavior, which is almost never happening in the movie. This guy spends the first 40 minutes of exposition being shit on for doing things like wanting people to do quality work, or showing up to work at all. He’s all about this community narrative, and he gets shit on for it. So when somebody rewards him for doing something for community, I saw that as a pretty big win for him. But I’m not sure what that’s doing for the sexuality narrative. And I don’t think it did anything demonstrable for him either, because it never came up again, and he didn’t pursue her at all. It was just this little mini reward sequence, like, “You did a good thing for others, well done.” And then he moves on to become a mass murderer.

Erika:

Disagree with me, but I wonder if this is… I don’t know that this was meant to be a film, this is a recurring kind of theme in the podcast, in the films that we’ve watched, this wasn’t meant to be a film about mental health or mental illness. This was meant to be a film that brought sex and murder together, and this psychosis trope was sort of the thing that conveniently bound them together. And so I think that helps to explain some of the chaotic readings, the many, many, many possible readings, is like, yeah, we could read this a lot of ways because the creators were not intentional.

Jeff:

Right, yeah. Yeah.

Sarah:

It’s like “the curtains are blue” problem, where the curtains are blue for any reason you want it to be blue, really, if there was clearly no intentionality to the reason why the curtains were actually blue.

Erika:

Okay, well, that brings me right to the last thing that we absolutely must talk about in this film, which is just the ending. What? What? Because was that in… Help me out here?

Sarah:

This broke me as a film theorist. I’m still thinking about this.

Jeff:

So for my first question, Philip does not narrate any of the other parts of the film, correct?

Sarah:

No.

Jeff:

But Philip narrates the end of this film.

Sarah:

Yeah.

Jeff:

What?

Sarah:

Because Harry has exited this film at this point. And at first, my first impression was when Philip strangled him, the rest of the sequence was actually a dream sequence, and this is what Philip is imagining. And then when the film abruptly ends after, am I allowed to say rape van? Because that is clearly a rape van.

Jeff:

There are no windows.

Sarah:

Okay. So when the rape van takes to the sky, like Santa’s sleigh into the night, where it was like…

Erika:

With Santa’s sleigh spray painted on the side.

Sarah:

Yes.

Jeff:

Yes, it is a Santa rape van, if we’re going to be fully accurate.

Sarah:

It was a very recognizable sleigh, I’ll give them points for artistic integrity on that. So the rape van ascends into the sky. And then I thought it is totally possible, given the other plot lines in this film, that this is not a dream sequence, and Harry actually is ascending to some kind of higher power due to the actions he has taken on Christmas Eve here.

Jeff:

Okay, wait, I need to step back here. Okay, so are you suggesting that after performing the proper blood rituals, you will become Santa?

Sarah:

You may or may not actually become Santa Claus if you are enough of a Marxist and you offer up enough bodies of capitalist hags. I don’t know. I was like, “This has got to be some kind of hazy, dream-like sequence,” which would be a nice reference to the fact that they were trying to deal with psychosis, but they weren’t trying to deal with psychosis. They were trying to deal with this kind of menagerie of illness symptoms, and then somebody said, “What if it was all a dream?” And had they actually committed to psychosis, that would be a really interesting ending. But they didn’t.

Erika:

The way that that scene plays out, it’s almost like symbolically he’s just fully lost it, right? He’s driving into the people, he’s chaotic, he’s haphazard. He’s just fully lost it. But it’s almost like he achieved his… He’s ascending because he achieved…

Sarah:

You will go to heaven if you kill capitalists for the greater good, yeah.

Erika:

Right. He did, he pulled off the Robin Hood, anti-Scrooge… He did it.

Jeff:

Wait, so are you saying that this movie was the original All Good Dogs Go to Heaven?

Erika:

That is what I’m saying, yes.

Sarah:

Yes.

Jeff:

So I think it is time for us to play our old favorite game of name that trope. And this film did have some tropes that we saw that are fairly common, I think, but also some original ones that we haven’t seen yet on the podcast. So, first and foremost, we have obviously this disabling event must be seen, must be filmed. We have this moment, has to be seen. There has to be an origin story, because disability is a thing that happens. You are normal until you’re not. And that is definitely upheld. As far as we know, Harry was normal until he saw his mom getting it on with Santa.

Sarah:

But he didn’t. Okay, this is my problem. He didn’t even see that though. He saw Santa kind of playing with her pantyhose. That’s all he saw. And then he ran upstairs and then they actually resubstantiate that two different times later. If you make the mistake of thinking, “Well, maybe they got really rough after and they couldn’t show that,” because his flashbacks are to Santa feeling the pantyhose.

Jeff:

Yeah. Yeah.

Sarah:

I have a lot of questions about that.

Jeff:

There was a lot of moaning. I will say that there was…

Sarah:

There was a lot of moaning.

Jeff:

Throughout most of this film, there was a lot of moaning. There’s a lot of moaning throughout this film.

Erika:

Okay, this hardly even needs to be stated, but we’ve got the age-old trope of mad people as violent or revenge seeking, murderous. If you’re going to hurt people, it’s obviously because you’re crazy.

Sarah:

Classic, particularly for SMI, or serious mental illness, class illnesses, which is clearly what they were going for. They wanted some variant form of schizophrenia, or psychosis, or bipolar with psychotic features, and the straight line they draw between, “He grew up psychotic, therefore his initial instinct after getting angry is ax murdering,” is just endemic. I could spend every day of my life arguing against this trope, and I would never make a feasible difference.

Jeff:

Yeah, yeah. It’s deployed in the way that we so often just deploy… It’s above reproach, it’s just naturally accepted, so they don’t need to even explain it. It’s like, “Oh yeah, of course that’s why he’s doing this.”

Sarah:

And it’s not even an ’80s thing, which I think is worthy of pointing out. There was a hashtag that went viral, I think it was three years ago now. It was #IAmNotDangerous, and people with SMI class illnesses were posting a selfie and saying, “I have X diagnosis, and I have never once punched a person, nevermind killed a person. I don’t choose violence,” kind of thing. And how viral that went really made me stop and think about how I’m perceived in the general realm. I posted a selfie, and I am a perpetually teenage-looking, white-presenting female with really long hair that doesn’t help the presentation of not looking perpetually 19. And it got something like 1500 retweets of people just saying, “Schizophrenia can look like this too.” As if the image in everyone’s mind was Harley Quinn and Joker until encountering on the internet an image of a normal-looking teenage girl and saying, “Oh shit, there’s also normal people with mental illness.” And that seemed to be, at least on Twitter, this crashing of worlds moment, this hashtag.

Erika:

Well, it’s fascinating that you’re zeroing in on this perpetually 19 look, because that was the other trope that we’ve kind of talked about, but this madness or mad people as this infantile or innocent, you can be a killer or you can be innocent. These are your options.

Sarah:

Definitely. And I’ll tell you one of my trade secrets, I do intentionally lean into that when I’m posting online, because I’m aware of that stereotype. But I’m also aware that playing into people’s confirmation bias is an excellent way to make them believe what you’re saying, right? So if I’m willing to give you that win of, “Fine, I am a bit childish. Fine, I am a bit young looking,” or I’ll lean into that myself, then when I’m making more complicated arguments about psychiatrization, or why forensic mental health methodologies aren’t working, I’ve given you that win to kind of breadcrumb you to follow me along on these higher-level arguments. And I do that completely on purpose. There is a relationship between me looking in the mirror and me presenting myself online, right? I think there are ways to use that… “Against” is the wrong word, but kind of against people in order to get them to complicate their belief against SMI class illness being this pervasive, bad thing that is a fail state condition.

Jeff:

So we’ve talked about the serious stuff, we’ve done some academicizing, if that is a real word. I think it’s time now for us to get a little trivial. So when we look at this film, you might remember me from such films as… Christmas Evil was written and directed by Lewis Jackson, who you’ve probably never heard of, in part because Lewis went on to do predominantly arthouse type pornography films that are very strange, as far as I could understand, and also very difficult to find. Having said that, our main character, Harry, is played by Brandon Maggart, who went on to do a ton of bit parts in television. Honestly, if you have watched a television show, Brandon Maggart has probably been on one episode; a very extensive IMDB. But was also, famously, in Robin Williams’ film, Life According to Garp, which I would like to believe now is a sequel to this film.

Sarah:

To be fair to Brandon Maggart, he was genuinely good in his performance. He was given a terrible script, and he did what he could with it.

Jeff:

Yeah. Oh, he was compelling throughout. Fully different person, contrary to what they looked like, Jeffrey DeMunn, who played Philip, is, I would say, probably the most famous to come out of this thing. It’s stated it has lots of bit roles, but has also been in horror films like The Hitcher and The Blob. Was also in The Green Mile, so we have a little bit of locked up institutionalization, disability, mental illness going on here in the Jeffrey DeMunn-verse.

Erika:

All right, and I guess that brings us onto production facts. So this film was originally titled, You Better Watch Out. I think it would’ve worked well as a subtitle.

Sarah:

Okay.

Erika:

Christmas Evil: You better watch out. Who knows? Maybe the sequel is coming.

Jeff:

Still waiting.

Erika:

We can only hope.

Jeff:

Still waiting. 40 years later, we’re still waiting.

Erika:

Also, apparently this film was confiscated during the video nasty panic in the UK, as a film that was deemed obscene, which I know… I think film representation has come a long way in 40 years, but I think looking back to the ’80s, it’s probably pretty obscene.

Jeff:

Yeah, well, I think the fact that it was also written and directed by someone who predominantly had a background in pornography may have played a role in that. But I also wonder if it’s like anytime you combine sex and violence, I think that was immediately triggering people. But yeah, it was confiscated, not convicted as far as I know. They were like, “You can’t have access to it, but we’re not sending Lewis Jackson to prison.”

Sarah:

I am 98% sure, and I did not backtrack because I just didn’t want to, but that there is a full-frontal muff shot in this movie, which is something that I see…

Jeff:

And she’s wearing pantyhose.

Sarah:

… very, very rarely. And when I read that it was confiscated, my mind immediately went to that take.

Jeff:

Yeah, she’s wearing pantyhose.

Sarah:

Okay.

Jeff:

She’s just putting her pantyhose on, and then she turns to him in a dramatic fashion.

Sarah:

Those are see-through pantyhose, that is… Even among films getting made now, I cannot account for too many full-frontals of female parts.

Jeff:

Yeah, no. I think this movie, if nothing else, one of the things I felt as we were watching it, and I think it’s explained a lot by Lewis Jackson’s oeuvre, is it’s like the film couldn’t decide if it was supposed to be horny or horror, and couldn’t figure it out. And so it just oscillated between the two, which made it very confusing and strange, I think, as we watch.

Sarah:

Sexuality was the horror the whole time.

Jeff:

So as we always do on Invalid Culture, we have to rank our films, we have to rate them, we have to appraise them as academics, as scholars, as scientists, and we have a completely empirical, fully rigorous grading system, which we use to evaluate our films. So as always, we will be ranking this film based on four quadrants, right down a scale of one to five. Like golf, the lower the score, the better it is for the film.

Okay, our first question, on a scale of one to five, with five being the least accurate, how accurate does this film portray disability?

Sarah:

Okay, so I have two different answers to my take on this scale, because the institutionalization scene, I think every time I’ve tried to say that, I’ve bungled it up, that’s amazing, is actually phenomenally well done. It’s really, really accurate to a point where you would’ve had to have completed outside research to really understand what’s going on in that scene. So in that way, that’s a one. But the protagonist of the movie does not make any attempt to adhere to any kind of real life embodiment of mental illness beyond, maybe, if you count his depiction of social anxiety. So generously, it would be a four. It’s probably closer to a five.

Erika:

All right. So I had, basically, a very similar read to what Sarah’s just laid out, but just in terms of scoring, I sort of balanced that out, went middle of the road, with a 2.5.

Jeff:

Yeah, I also tried to balance it out, but I was a little harder on it. I gave it a four. My starting point on this feature was a lot higher on the scale, so I gave it a four out of five. Okay. This one, I am curious about how this one’s going to turn out. Scale of one to five, with five being the hardest, how hard was it to get through this film?

Sarah:

I would say a three, and I’m going to say a three because there were some genuinely interesting moments that we already discussed, like the Marxist labor dialectic side plot, and the whole bit that I don’t think we spoke about, about the torch bearers. That was hilarious, I’m not sure it was supposed to be funny, but that made it more watchable for me. And obviously the bits where he is actually interacting with the children is actually quite heartwarming. I genuinely enjoyed those scenes where he’s not just being relentlessly bullied, or killing people, or being told by his family members that he is worthless and a failure, because he is actually really good at interacting with kids. So I don’t know, I come out in the middle on it.

Erika:

So for me, it was brutally difficult to get through this film. I have a hard time getting through movies anyway, but I was literally checking every five minutes to see how much time was left. And I will throttle back just slightly because yes, the anti-capitalist labor narrative kept me in it. So we’ll give it a four. That’s a four for me.

Sarah:

Particularly the 40 minutes of Tolkienesque exposition. That was a hard decision for this film to sustain, because there was just so little plot to expose in this 40 minutes.

Jeff:

So I’m going to expose something about myself here. So I gave this a one, because I felt it was thoroughly enjoyable to watch this film, because it was so strange and so bad. I thought it was phenomenal. One of the things we haven’t even talked about in this podcast, which is something, is the entire police subplot in which they’re arresting all the Santas…

Sarah:

All the Santas!

Jeff:

… all around [inaudible 01:10:02]. There’s a whole other part of the thing, which was phenomenal, and so funny.

Sarah:

They do The Usual Suspects lineup, and they’re all just yelling, “Merry Christmas everyone”.

Jeff:

Yes! Yeah, there were some things that were really fun. I really enjoyed all of the labor stuff in this, I thought was interesting. And how often do you see someone get stabbed in the eye with a toy soldier, and then someone else get axed to death with a toy ax? That’s a hard one.

Erika:

Don’t forget the throat slit with the tree star.

Jeff:

Yes, also that as well.

Sarah:

Yes. The thematic play of all the weaponry used in this film, I really appreciated the commitment. He worked at a toy factory, he was incredibly invested in making his own toys out of palladium silver in his own home workshop, and he used those abilities to enact incredible ultraviolence, in the Clockwork Orange sense, against people he deemed against the concept of true Christmas.

Jeff:

And become Santa as a result.

Sarah:

And become Santa, yeah.

Jeff:

That’s a one. That’s a one. Okay, so this one I struggled, personally, immensely with answering. On the scale of one to five, with five being the max, how often did you laugh at things that were not supposed to be funny?

Sarah:

Yes, I was laughing all the way through this movie with the person I watched this with, and I don’t think there were any jokes actually written for this movie. It was funny entirely unintentionally. I guess it would have to be a five, right?

Erika:

Yeah. I’m following suit on that. It’s a five for me.

Jeff:

Oh man. So apparently this is the episode where I am fully out of sync with the other judges of this film. I gave this one a three, because…

Sarah:

How is that possible?

Jeff:

I think that a lot of the stuff, I think, was supposed to be funny. I think there were things that we were laughing at that were intended to be jokes, I think. But that’s where I was struggling, because I was like, “Well wait, were we supposed to laugh at Moss Garcia for having negative body hygiene?” Because that is a hilarious thing to say about a child objectively. But was it supposed to be funny? And I honestly don’t know if it was supposed to be funny, but maybe? But I think there was some other stuff that was definitely supposed to be funny.

Okay, our final question, on a scale of one to five, with five being the most, how many steps back has this film put disabled people?

Sarah:

It’s hard to give this movie a rating, because it’s following a strong, and long, and continuous, and endemic tradition of depiction of SMI class mentally ill people, right? So if I condemn this movie’s depiction of it, I’m kind of not being fair to film in general, because in order to get funded, I’m sure it would have to cohere to some norm of how we depict mentally ill people. But it’s also enabling that architecture, right? So when I think of this film alongside films that I think do psychosis really well, like Last Night in Soho, that came out last year at TIF, that is the most accurate depiction of schizophrenia I have ever seen on film. But what it had to do was interrupt 50-some-odd years of schizophrenic depiction on film. So you had to get people like Anya Taylor-Joy on the cast in order to make that realizable. So am I surprised that this was a brutal, atrocious depiction of mental illness, and madness, and SMI class illness? No. Can I indict the film for that reason alone? I think it’s more complicated than that. So maybe a 2.5?

Erika:

I went four on this one. I felt like I gave it a little bit of credit for maybe exposing an unlikely audience, perhaps, to the history of institutionalization, I thought that was a redeeming factor. But by and large, it was just like that repetition of the story, the just painfully familiar tale of madness and violence. That’s where my score came from.

Jeff:

Yeah, I actually also gave it a four for almost the exact same reasons. The film might not have taken us any step forward, which is too bad. But I definitely think if you watch this film, you’re probably not going to have great thoughts the next time you see a mall Santa and are like, “Is he mentally ill? Am I about to get stabbed?” Yeah. So I’m going to give this one a four.

Erika:

I’m dying to find out if this lands in “a crime may have been committed”, please let it be so.

Jeff:

The scores are in, the tally is done. I am proud to announce that with a score of 43, Christmas Evil is “a crime may have been committed”.

Erika:

Woo!

Sarah:

Agree with that. Bad film. Even when we deconstruct it the way we deconstruct it, it really cannot be saved from its fatal anti-heroic flaws of being just so guilty of the most [inaudible 01:16:21], unfair mental illness representations.

Jeff:

I think we’re going to put a big asterisk on this rating.

Sarah:

Really?

Jeff:

Because it was largely carried by the fact that I am a dysfunctional person who likes bad movies. Without my ability to get through the worst of the worst, this would have been the “Jerry Lewis Seal of Approval”. So, “Crimes Have Been Committed”, with a slight asterisk, because Jeff is a broken person.

Erika:

Aren’t we all [inaudible 01:16:57] beautiful [inaudible 01:16:58].

Sarah:

I think you’re a beautiful person. That’s true.

Jeff:

That’s the point of this show, we’re more beautiful for having been broken, which is a reference that you’ll understand come February.

And this concludes another episode of Invalid Culture. Thank you for joining us. I hope you enjoyed it, or not. Do you have a film you would like for us to cover on the pod? Or, even better, do you want to be a victim on Invalid Culture? Head over to our website, invalidculture.com, and submit, we would love to hear from you. That’s it for this episode. Catch you next month, and until then, stay invalid.