What if seeing puns became a movie?

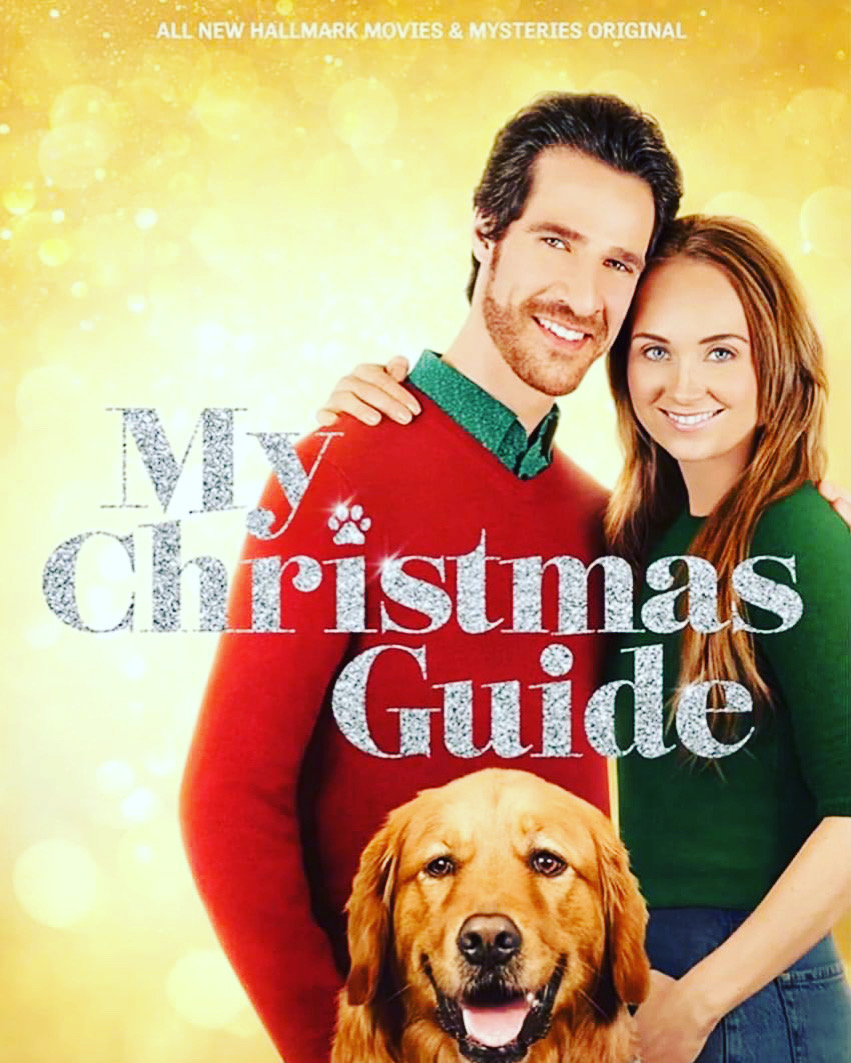

Anyone can see it is Christmas-time, but will a blind man spot the benefits of using a guide dog? Do you need eyes to be a man and a professor? In our 2023 Christmas special, Jeff and sar peep the recently released Hallmark Channel made-for-television film My Christmas Guide. Join us in gazing into the Christmas vomit abyss that is this romantic (?) holiday thriller woke-a-thon.

Listen at…

Grading the Film

As always, this film is reviewed with scores recorded in four main categories, with 1 being the best and 5 being the worst. Like the game of golf, the lower the score the better.

How accurate is the representation?

Jeff – 2 / 5

sar – 1 / 5

Total – 3 / 10

How difficult was it to watch the movie?

sar – 4 / 5

Jeff – 5 / 5

Total – 9 / 10

How often were things unintentionally funny?

sar – 2.5 / 5

Jeff – 3 / 5

Total – 5.5 / 10

How far back has it put disabled people?

Jeff – 2.5 / 5

sar – 4 / 5

Total – 6.5 / 10

The Verdict

Regrets, I have a few…

Podcast Transcript

Jeff:

Welcome to Invalid Culture, a podcast dedicated to excavating the strangest and most baffling representations of disability in popular culture. Unlike other podcasts that review films you’ve probably heard of, invalid Culture is all about the abyss of pop culture, adjacent media that just never quite broke through because well, they’re just awful. Now let’s dig in to the worst films you’ll wish you never knew existed.

Mvll Crimes [musical interlude]:

I’m arguing with strangers on the internet // not going out today because I’m feeling too upset // I’m arguing with strangers on the and I’m winning…and I’m winning!!

Jeff:

Welcome to a special bonus edition of Invalid Culture. As always, I am your host Jeff and I am joined today by past podcast and new co victim. Sarah, welcome.

sarah:

Hello. Thanks for having me.

Jeff:

Are you excited to be here again?

sarah:

Obviously I haven’t been here since the last Christmas special.

Jeff:

Yeah, we’ve been on a bit of a hiatus, but we thought it’s Christmas time, it’s time for family, and so it was time to bring you back for another moment of torture

sarah:

Time for more terrible Hallmark films vaguely about disability.

Jeff:

Absolutely. That’s the time of the year. It’s the reason for the season, I believe. So this year to ring in the festive season, we were given a present by the Hallmark Channel. Once again, a Hallmark has decided to dip their giant toes and walking sticks into the world of disability and media or film. This time with the 2023 November release of My Christmas Guide. Now from the Box, My Christmas Guide is allegedly a movie about “a college professor who connects with a guide dog trainer after losing his eye sight and a adopting a seeing eye dog.” That’s essentially the high level, but we’re going to dig a lot deeper into this movie. Before we do though, as I said, this is a Hallmark movie, made for TV, is released in November. It was written by Keith Hemstreet. Now he has a very interesting history. He has written a ton of movies in the last year that all appear to be romantic TV shows, things like a Royal Christmas Crush also came out this year and Love in Glacier National also cave out this year, so Keith Hemstreet just banging out the romantic TV movies. It was also directed by Max Mcguire. Max splits their time between Christmas movies, Christmas by Design, Record Breaking Christmas, The Most Colorful Time of Year and murder movies. Other movies he’s done: Abducted on Prom Night, The Good Wife’s Guide to Murder, the Ice Road Killer, et cetera.

sarah:

I want him to combine those two genres. I feel like he would be the guy to do it. I want the Ice Road Christmas killer.

Jeff:

Yeah, I love it. I love it. I thought that was phenomenal. What a career path. Great. Now, unlike most films that we do in this podcast, this film actually features an actually disabled actor playing their own character. Ben Mehl is playing the main character Trevor. Ben is disabled, is blind, and is best known probably for his role as a librarian in Netflix’s show You and he’s noted in an interview that quote, my role on you was my first role where I haven’t had to pretend to be able to see more than I actually can. He went on to talk about this movie in particular, stating that to be able to represent a character who has vision loss while personally having similar experiences attracted me to the role. He says that he hopes that he’s able to raise people’s understanding and awareness of the different experiences of disabled people and wants audiences to always be reminded to be aware of disability. So that’s a little bit about who we have in our main character. Trevor, does that help you understand the movie better at all, Sarah?

sarah:

No, but I really wish that he went for the seeing pun in that based on the script.

Jeff:

Yeah, not to always be aware, but to always see to

sarah:

See disability wherever we go.

Jeff:

Absolutely. Our romantic lead, a female lead is played by Amber Marshall, who is our guide dog trainer. She is from London’s own, I should have said London’s own Amber Marshall from London, Ontario, best known probably for her role as Amy in CBC’s Heartland. So we’ve got some real Canadian media legends

sarah:

Here. That’s something I’ve actually heard of. That’s pretty cool.

Jeff:

And then there’s a third character not in the Love triangle, but critical to the film, which is Trevor’s daughter.

sarah:

Oh, I thought you were going to say Chainsaw.

Jeff:

No. Chainsaw is the most important character to me.

sarah:

He was also surprisingly important to the Love Triangle, though. Don’t sleep on chainsaw.

Jeff:

Don’t sleep on chainsaw, but Chainsaw, unlike Ava Weiss who plays Annie, Chainsaw was not in the film Moonfall, which Ava Weiss was. She is in the terrible possibly amazing film Moonfall.

So just off the absolute top, Sarah, just really quickly, how did you feel about this movie?

sarah:

If you excuse all of the really poorly done references to the fact that they’re trying to do an inclusivity film, but through the lens of extreme exclusivity, they were obsessed in every scene with pointing out that the protagonist was blind. He is different guys. By the way, this is an inclusivity film. I was actually much more fascinated by the love triangle angle because I am convinced and we can argue about this, that the true victim of this film was Chad, the heavily gaslit boyfriend. I really feel like he lost a lot in this, and you’re supposed to just go with it because he is a nothing character and I disagree. I’m coming out in defensive Chad here. What did you think,

Jeff:

Jim? Chad? Yeah, I would say honestly, and I apologize to all the Hallmark fans out there, this was probably one of the most boring films I’ve watched for this podcast.

sarah:

It was hard. That was a tough one.

Jeff:

It was so slow and nothing happens. I think it’s the only redeeming quality, thank God. I don’t know if this is cinematographer decision or the director’s decision, but the number of Slowmo glamor shots of the Guide back of

sarah:

Max, yes, was the

Jeff:

Only thing that helped me get through this film.

sarah:

We were counting them at one point.

Jeff:

There were many. That was great. That was great. I have huge, huge love for that, huge love for chainsaw, and while those are our opinions and our sort of overarching views of the film, we are not the only ones who have opinions views about this film. There are of course critics that have written about this film that have analyzed it, have spoken about it, and let’s hear a little bit from them. And so our first critic that I wanted to talk about is Brett White. Now, Brett White wrote a very long thing about this film for Decider. It’s basically a blog that lets you help to understand if you want to watch a movie or not, which I think is actually a pretty clever, I pretty clever conceit. This is what Brett White had to say about his experience with the film. There’s a lot of patient character work that you only realize was character work, right? As the script is making big emotional moves, he goes on to say, interestingly, Trevor feels unlike any hallmark hunk we’ve ever had, primarily because he has a brainy profession and doesn’t exactly brood smolder or flirt with our leading lady. Trevor’s a different kind of leading man, and Ben is fantastic in the part

sarah:

I’m desperately trying not to ask for his background, but I’m thinking definitely Laurier and definitely film studies, and I can say that because I did Laureate film studies. I do like, what did I call her? I called her b-list Santa Stark, the protagonist love interest. She was probably the closest thing to actual talent in the film, but the rest, I don’t know, agree to disagree.

Jeff:

I particularly like this quote because it seems almost like Brett White is kind of calling Ben not attractive, is sort of like he’s

sarah:

Not my type.

Jeff:

He’s smart. He doesn’t brood or smolder or flirt.

sarah:

I needed a positive adjective and the one I went with was smart.

Jeff:

He’s a brainy professional,

sarah:

But even, okay, can we do quick rants?

Jeff:

Yeah,

sarah:

Even the scenes where they let him, okay, so context, they let him be some kind of amalgamation between sessional professor and full professor depending on what room he was standing in. That’s another thing. But if you take for granted that he is a legitimate English professor, every single time he does a scene where he’s supposed to be very bookish and knowledgeable about classical texts, he blows it. It sounds like he just read it the other day and he’s nervously commentating on it, and everyone around him immediately dismisses anything he says about literature to be like, no, your only legitimate character trait is that you’re blind. We don’t care about this book thing.

Jeff:

Yeah, I fully agree. I feel like the one thing I didn’t believe the most is that this man was a professor.

sarah:

Oh yeah. At all. He did no research for that role.

Jeff:

He had the satchel, he had the satchel bag…

sarah:

He did have the satchel, he did the, what’s it called, mock neck turtleneck. He did that a couple times and he attempted to speak in professional situations about literature, which I guess on its face I agree with, but I’ve heard sessionals do a better job than this. Maybe full professor.

Jeff:

Yeah, it sounded like chat GPT writing a professor character. Actually, I think that would probably be better, but yeah, so Brett White, he is a fan. He liked it. It’s a different kind of leading man. He’s not a hunk, he’s not brooding, he’s not smoldering. He doesn’t flirt, but he is fantastic. This was not the opinion however of CGVSLewis on IMDV who gave this a five out of 10 title in their user response quote, A guide dog finds a home for Christmas and a woman boots or obnoxious boyfriend. This is the title of the review.

sarah:

I already disagree, but continue. Yeah.

Jeff:

Okay, so I don’t know what CGVSLewis sounds like, but I assume it sounds a little bit like this: Also, as I keep mentioning, I like my entertainment as entertainment and not social justice causes. I work all day at a hospital as I have for 30 years, and I don’t want to come home turning on my entertainment to be the lecture. Granted, this was a soft lecture, but it still took several opportunities to hit us over the head with the challenges faced by those who are mobility impaired. Guess what? I see it every day at work. A big part of our job is education, and I would like to just be entertained when I come home tired and with sore feet. I did really appreciate the classic literature quotes. That was my favorite part.

sarah:

Where was the classic literature quote? Oh, in his lecture where he started reciting Chaucer from memory or something?

Jeff:

No, you were giving them way too much credit. He had a quote from To Kill a Mockingbird of one kine. He had a quote from Mark Twain and he had a quote from Ellison, which is probably the most not high school English class book, Invisible Man, that they referred to.

sarah:

Oh I’m hoping he was quoting American Psycho. That would’ve been great.

Jeff:

No,

sarah:

That would’ve been a nice Easter egg.

Jeff:

I love the fact that somebody went on a anti woke rant about a Hallmark movie, about a guide dog,

sarah:

The absolute wokeness of mobility impairment.

Jeff:

I also love that part of their job is education, but they don’t know that this would not be defined as a mobility impairment.

sarah:

Yeah, yeah. It checks out actually.

Jeff:

Okay, I’m sorry. I think we need to talk about this film. So let’s take a little wander through the story of my Christmas guide as best as I understand it.

So our movie begins with the introduction of Trevor, a Dickens-obsessed professor of “Classic Literature” in <insert random American town that is totally definitely not St. John’s NFLD>. Losing his vision and wife, no relation, several years ago has left him disoriented. After damaging his face walking into a non-OSHA compliant construction site, there are questions about if Trevor can continue working because there is apparently no way to make a 6-month long sidewalk construction project safe for blind people. One day, while picking up his dog-obsessed daughter from school, local guide dog trainer Payton is out for a stroll and observes Trevor aggressively serving Blind Man™. After staring silently at Trevor from across the street for an entire scene, Payton decides to intrude on this stranger’s life, demanding the school secretary give her dog guide service literature in a clear violation of school stranger danger rules. After some debate about whether or not a dog would make Trevor’s life easier or harder, he eventually relents and begins training to acquire extremely photogenic guide dog, Max. This training largely consists of being guided around town with Payton cosplaying as a harnessed dog and giggling maniacally. What are your thoughts on the beginning of the film, Sarah?

sarah:

That’s almost hard to characterize. I think for the first, at least half of its runtime, I was kind of confused as to what the movie was actually about because I think I was looking for, because when we watched Christmas Evil last year, there’s a fairly robust plot line. There’s this trauma circuit between the brothers and then there’s this B Ark where the brother tries to redeem himself by this Christmas party. There is virtually no blot in this film in comparison to last year’s film. So I kept waiting for the moment of intrigue, but I think upon reflection, the moment of intrigue was actually Peyton forcing herself into Trevor’s world via this kind of weird play at his daughter’s school to get him to adopt a dog because she’s the one who trains the dogs. But then I don’t even know why she knew what school to go to. It stands up until you start thinking about it and then you’re like, wait, that doesn’t make any sense whatsoever.

Jeff:

Yeah, I think they were leaving the school. I think that’s how she knew that was the school that

sarah:

The daughter went to, and she just shows up with disability information. By the way, in case you’ve only been blind since yesterday, I actually train seeing eye dogs and you can have one. Yeah, I didn’t like it. I didn’t like the setup.

Jeff:

Would you say that Peyton is a crafty capitalist or is she a conniving capitalist?

sarah:

Peyton is garbage, so a capitalist in general from the Marxist,

Peyton definitely coming out in favor of getting more clients for her dog training school, but she’s also spending most of the movie gaslighting the shit out of her boyfriend to think that he’s a terrible boyfriend so that she can break up with him with zero regrets or remorse in order to be with this blind guy that she just met, who I guess she thinks is hot or has a charismatic personality or both of which he actually exhibits neither. So I’m not sure what she’s seeing, but she’s definitely seeing more than what she sees in Chad, and she spends so much of this film and you were with me and I was so mad just telling this guy over and over like, you are no good. I don’t like what you’re doing to me. While he’s trying to be the kind of prototypical supportive boyfriend, they even named him Chad. They did him dirty, but they didn’t even make his villain arc good.

Jeff:

So let’s talk about that. As our story continues to unfold, we discover that Peyton is in a strained relationship with her golf obsessed boyfriend, literally named Chad, who is leaving her for Christmas to go golfing in Florida with his friends and chainsaw. Yes, these are their names. I should clarify here. Chad does not look like the kind of person who would have friends named Thurp and Chainsaw. Chad very much looks like the type of person whose friends would be named like Huston and Beauregard perhaps

sarah:

And Derek.

Jeff:

Yeah, absolutely not. And trades up. No. So as Peyton and Trevor start to work together, sparks begin to fly that even a blind man could see that maybe there is something here. Trevor’s daughter, Annie is now starting to get bullied at school because her dad is blind, but through the miracle potential of Peyton becoming her new mommy, she almost completely ignores a bully. Instead of wandering down the school shooter pathway, Peyton and Trevor continue to get closer with Trevor showing Peyton around the only campus in America where Christmas is clearly winning the war on Christmas. Peyton eventually decides to do a totally normal professional relationship thing and introduces Trevor to her father at a Christmas charity event because Chad has bailed on this commitment in order to golf at the number one golf course in Florida.

sarah:

So one, I think we decided partway through the film that although it seems to be introduced from Peyton’s perspective that Peyton and Chad are in a fairly serious relationship, it starts to kind of erode by the two thirds mark, and it seems to me at least that they’re in a way more casual arrangement than Peyton seems to think from the interactions they’re having. But even then he’s doing stuff like calling her from Florida to check in and ask for permission to stay longer with his friends and stuff, which to me seems like solid boyfriend behavior and she gets off the phone rolling her eyes. I can’t believe he would ask for more time. I can’t believe he’s not coming home to me right away from this trip that has clearly been prearranged for months. I don’t know. I’m back on this.

Jeff:

Sure. I mean, I will say there was the swap out where he implied that he had this big surprise for her and then he brings her outside and the surprise is that he has bought himself golf clubs.

sarah:

Surprise baby. I’m leveling up my golf game.

Jeff:

So I, I think this is the tension that they’re trying to draw out and this is that he keeps on insinuating that something’s coming to her, but it never is. It’s never coming. But I think you’re right in that there does appear to be this clear disconnect between where Chad thinks the relationship is and where Peyton thinks it is, because Peyton thinks it’s like we’re married or we’re about to get married, and Chad is sort of like, I might see you next week maybe

sarah:

Pretty much. Peyton also seems to not respond at all to emotional dialogue cues, which he gives a ton of, and at least among my female friends, we talk a lot about how that’s maybe missing in some relationships. Chad’s got it in spades, even if they’re just casual. He’s got the full social worker routine about how validated does this make you feel, or I’d like to remind you that you’re special to me kind of thing. I don’t think a lot of people have that, and she’s just sitting in the car like, Ugh, insufferable. And I’m like, really? Is it insufferable though?

Jeff:

Meanwhile, we have some really scintillating, some scintillated romance sparking between Peyton and Trevor. I will give this movie credit. They did not do the typical trope of the blind man touching the woman’s face and saying, you are beautiful.

sarah:

I’ve felt sure I was waiting for that.

Jeff:

They did not do that. What they did do instead was have Trevor essentially say, you smell real pretty. There is a scene in which he essentially says, well, I can’t see you, but you smell pretty and then asks if he smells pretty.

sarah:

He actually kind of demands that he complimented.

Jeff:

And I’d like to know how many of your relationships Sarah have started with an exchange of smell description?

sarah:

You know what? I think many of my past relationships have actually started on the seeing description how drop dead gorgeous I am. That is a joke. So maybe the joke is because he can’t see, hey, he’s got to start with smell, but he has taken that way too seriously. It gets a bit weird.

Jeff:

And I also wonder, I mean that the implication is that she has a lovely perfume or something that she’s wearing. I would’ve given this way more credit if she had been eating smart food before they met and she smelled like smart food. That is an appealing smell. I would That’s true. If you smell I smelled like smart food, I might ask to be out on a date. That’s true.

sarah:

If you follow it up with offering that smart food to me, yeah, I’d go places with you no problem if

Jeff:

You’ll share the smart food.

sarah:

Exactly. That’s fair enough. I’m getting right in the car.

Jeff:

That’s actually the surprise maybe that Chad had for the end of the film of family sized bag of smart food, perhaps.

sarah:

Perhaps.

Jeff:

Perhaps. Yeah. So we move forward in our film. We’re finally at the end. Chad has now returned from his golf trip only to discover that his girlfriend is spending literally every moment of her life with this clumsy blind man that she had lured off the street confronting Trevor Chad assures Trevor that Peyton is just not that into him. This is just how she is with all the blind people, so he shouldn’t get the wrong idea. Trevor, of course, has a masculine identity crisis and after being forced to go on leave because the school cannot figure out how to make this construction site accessible despite Max clearly having a guide dog that can navigate it has to go on leave. This is the final straw for Trevor whose big sad boy energy results and giving up on everything going home to sulk and returns the dog that he has been living with for weeks.

This tension is almost immediately resolved when a recording of Chad and Trevor’s conversation is revealed to have been captured on the guide dog business security camp. So Peyton dumps Chad runs to Trevor’s arms and assures him that he is a real man and definitely like a professor, even though he is blind, Trevor’s child now, a young offender after assaulted her bully in the cafeteria with a cupcake, is excited for Christmas and spends the final scene watching her dad make it out with new mommy on Christmas Day, which I think makes this film a prequel to Christmas evil.

sarah:

That was a bit of a wild crossover right at the end.

Jeff:

I did not plan this to be essentially a two part that was beautiful. This is evil, but it worked out perfectly. So there’s two things I want to talk about in this part of the film. So thing number one that I want to address. What are your thoughts about the fact that the university forces Trevor to go on a two-term leave because they cannot make this construction site accessible?

sarah:

I actually thought that this is one of the more realistic moments of this otherwise relentlessly unrealistic film because if you do believe and it flip flops throughout the whole film, but if he is a sessional instructor, he would absolutely lose those terms if somebody else could make their lives easier and replace him. So that is completely believable. And in that instance, if he’s been working term to term as a sessional, he probably would have to return the guide dog. And this is an argument I made to you before because all the upkeep costs associated with the CNIB and dog raising and dog training and paying off the dog as well as just all the costs associated with keeping the dog alive, IE vet bills and food and whatever else, he probably legit can’t afford the dog if he loses his sessional contracts. So that was, I don’t think they meant for it in any way to be that realistic. I think it was just a convenient plot point. But from a labor studies perspective, that was probably the most interesting part of the film.

Jeff:

So I had a similar take, but maybe a little hotter than yours. I think on the one hand, I don’t think he’s a sessional because he does have an enormous office and it has a fireplace. It does. Which his office is actually bigger than his chair who is in a cubicle farm for some reason. He does. So he has an enormous office to himself that has multiple Christmas trees. His boss chair, I would assume maybe a dean is in UNC cubicle somewhere on campus. But on the one hand, it’s obviously completely absurd this notion that the solution to, I mean, there’s been a lot of construction in my life and I’ve never been told, well, you can’t come to work. We don’t know how to make it safe for you. There’s a absurdity to it, but at the same time there is this unintentional kind of nailed it where not even just universities, but I think a lot of organizations, it’s exactly the type of baffling response to inaccessibility that rings actually weirdly true.

sarah:

Right. I was going to challenge you on that. Do you really not believe no one responds

Jeff:

Exactly. No one responds to inaccessible situations in a rational way. The responses tend to be really irrational and bizarre, and so in that way, this is actually maybe a really accurate representation that maybe there is actually a bit of reality to be like, yeah, I actually could see an institution being like, well, I don’t know what to do, so we’ll just pay you to not be here.

sarah:

I thought it was totally realistic. Do you remember what happened a couple years ago at u Guelph where the elevator stopped working? So they emailed all the students in wheelchairs and they were like, yeah, take online classes. We’re not fixing the elevator quickly, don’t come. And all the students were like, that’s completely unreasonable. And they didn’t fix it until they got roasted in the news for it.

Jeff:

Yeah. And so think in that way, it seems absurd, but it actually is maybe not completely out of the world. I will say it does seem like an overreaction given the scale of the problem. All we’ve seen of this construction is it appears they’re replacing sidewalk like pieces. This is not a major construction project by any means, and it feels like just a little bit of fencing is all it would take to make this accessible. But I digress.

sarah:

I would also argue that you are at an institution that has a disability studies department, so perhaps it’s easier for me to believe as being from an institution that actively hates disability, that we would fire those people instead of accommodating for them because we would never get a department like disability studies.

Jeff:

So this is the other question I have because they are really, really vague on their wording on what happens here because the way it’s framed in the film is that he just won’t be teaching for the winter term and the summer term that he’ll be taking two terms off and that decision is made and then five students write a letter to the boss and the boss changes his mind.

sarah:

Yeah, I forgot about that.

Jeff:

And reinstates, and so it doesn’t sound like they were necessarily firing him. It’s like he was going on leave. That’s sort of how they kept framing it, is that he had

sarah:

…and the students have a little solidarity protest about it.

Jeff:

Five of them, yes. I just want to put out only five of his students were willing to write a letter to say, you shouldn’t ban him from campus. Correct. Which seems like a low number, a really low number

sarah:

For an English prof. I don’t know. That also kind of rings accurate to me.

Jeff:

Yeah, I mean when they did do this shots of the students, there did only appear to be eight students in his class. Exactly.

sarah:

So five out of eight is actually great.

Jeff:

I also though don’t imagine many universities would do anything if five students wrote them. I think there’s a lot of universities that wouldn’t respond to a hundred students writing to them necessarily. So yes, there was though obviously that scene also killed me because clearly they were trying to do this whole sort of dead poet society like, oh, captain, my captain kind of thing, where they have the students marching into the office, but they didn’t have the budget to hire a lot of people. And so they’re like, well, we’ll have three people and one of them will hand in multiple letters and that’ll be our big protest maneuver. Then all the viewers will get their uplifting, all the students care about him. I felt really underdeveloped, I would say.

sarah:

I think the whole film felt a little underdeveloped. So in that sense, I’m with you. Fair enough.

Jeff:

Fair enough. So I think what we’re moving toward then is there are some tropes here in this film, some pretty well worn others, maybe not quite, but I thought we should probably talk a little bit about some of these tropes. So the first trope that I wanted to talk about is the requisite scene at the beginning of the film in which Trevor has to explain his disability because you Yeah, you

sarah:

Got to wonder why they went for the medicalization angle for something like blindness, because I think it’s fairly culturally accepted that there are some people who can’t see, and that’s kind of all the explanation you need.

Jeff:

They don’t into a surprising amount of detail.

sarah:

I want to see retina scans. I want to see exactly how much Trevor can’t see.

Jeff:

Give me the exact, why don’t you give us the camera view to show us stats, what he’s not able to see. Yeah. This felt weird and it felt weird in particular because of how much time the movie spends reminding us and showing us. If you cannot see

sarah:

From, he wears these ridiculous glasses just as a visual of, remember Trevor is blind,

Jeff:

Giant blackout, wraparound glasses, awful. Got the walking stick, always rocking the eye dog. Eventually he is surrounded by icons of blindness, and yet there needed to be this moment where he sits down for a very serious conversation to tell Peyton all about his medical history.

sarah:

Yeah, Peyton, somebody he literally just met.

Jeff:

Yes, but she smells good. So she does. She’ll understand

sarah:

Marker of trust.

Jeff:

Yes, yes. I’ve always wondered what would happen in my life if every time I met someone, 10, 15 minutes into the conversation, I started reading them out my medical chart and was like, alright before. And they’re like, this is a Starbucks, just make your order, please. And I’m like, no, you need to know about my formal muscular dystrophy.

sarah:

Pardon? It is

Jeff:

The big one.

sarah:

Exactly. The big one. We’re bringing that back.

Jeff:

Yeah. So I wonder, I feel like people would just tolerate it, but I don’t think it would make friends.

sarah:

No, I think people would uncomfortably wait for you to come to a complete stop and then they’d take a right hand turn.

Jeff:

They would no doubt of the relationship probably pretty quickly.

sarah:

Pretty quickly.

Jeff:

What I would love to see from a Hallmark movie is for them to just apply this as a standard for all characters, whether or not they actually have. So it’s like every character is introduced and then they’re like, you just need to know that I actually have dandruff and have my entire life, and I fought it and I was bullied for it. And it’s a thing that my scalp is so dry, medically dry,

sarah:

I’m the love interest and I have adult onset asthma and I’m going to relay for you the factors which make my life more difficult.

Jeff:

Yeah. I’m not really good at sleeping. My security rhythms are really off. Correct. And so I’m actually often really tired. And it’s a medical condition though.

sarah:

Correct. And the blind guys, are you trying to do an oppression Olympics here? I don’t give a shit.

Jeff:

You can take your C Pap machine and stuff it

sarah:

Chill out, buddy. At least you can see it.

Jeff:

Right. So that actually is a great segue to the second trope that I wanted to talk about. This movie spends a lot of time making puns around the word seeing exhausting and sight constantly. Everyone can see, obviously you can see if only they could see why was this intentional or was this Freudian?

sarah:

It had to have been because sometimes you can almost see the actors looking off screen or looking toward camera one or two. Did you get that?

Jeff:

I really wondered how in it, there were so many of them that at times I feel like this was just how the people wrote the script. This is just how they talk with this sort of idea of site being equivalent to knowledge that you must seem to understand. But then there were other times where they very clearly were leaning into it and trying to make this pun. Yes, but it was overwhelming at times. Yes.

sarah:

The equivocation of blindness and ignorance made this film really uninclusive for me. Not only because of how hard they went on it, but also how hard they went on his visual as his defining character trait is that he is blind. And if you know anything else about him, that’s just a bonus, which feels to me extremely uninclusive for an inclusivity film about, look at Trevor, he’s just like us. He has romance problems like us. He has to walk around traffic and construction like us. It just all rang really hollow when you add in all of those, I don’t know Tropey signals about, but remember he’s blind.

Jeff:

Yeah, absolutely. Yeah. I don’t fully understand why they felt they had to keep reminding us. And it may be because this is a made for TV movie. It’s clearly designed to sit within commercial breaks. So people are kind of coming in and coming out at any moment. And I’ll say, and I don’t know if this is a, I compliment to the film, but you could pretty much start watching this movie at any point in the movie and you would have all the information you need to understand what’s about to happen.

sarah:

It’s like friends, it doesn’t matter where you start.

Jeff:

No. You just jump in wherever and you’re like, okay, well this guy’s clearly blind there. People are mentioning it, obviously they clearly have something going on. Oh, her boyfriend’s name, Chad. So he must be bad. Yeah. Okay. So I think that there may be that element here happening where the form is requiring it, but I think that’s a very generous assumption and I don’t think that that’s probably what’s going on.

sarah:

I think that speaks more to how little plot there was. It was bizarrely simplistic even for a Hallmark film.

Jeff:

Yeah. Well, I think it’s important to remember the writer and the director of this film made by 18 movies this year. So I assume they probably wrote the thing in four days, maybe

sarah:

Four hours,

Jeff:

Maybe.

sarah:

Maybe filmed in four days across Cobourg all the way to St. John’s.

Jeff:

Yeah, yeah,

sarah:

Yeah.

Jeff:

The other trope that I noticed that really stood out to me in this film was the bully. So Trevor’s daughter, Annie is being tormented a boy at school who is constantly doing a pantomime of her father. So he is constantly walking around with his eyes closed, being like, I’m blind, look at me and walking into stuff or touching stuff, and Annie’s getting angrier and angrier. Eventually Annie will decide to smash a cupcake in his face. Annie is then suspended, expelled, punished for suspended, suspended for violence on school campus. Again, I think accurate and brave of Hallmark to stand up on the anti-retaliation things that happened in school. And then eventually she will save the bully because as we learned in Star Wars, there’s always a bigger fish and there’s an even bigger bully who is picking on her bully. But this bully wets the bed, I don’t know how Andy knows this, but this boy who clearly experienced trauma as a child and is now bedwetting as an older child, gets called out embarrassed. He runs off and the blind bully is now your dad’s pretty cool actually, and everything’s resolved. Sarah, why do you think whenever we have a disabled character, there is always a need for a bully to be harassing this person or their family?

sarah:

Okay, so I’ve only been thinking about this for 10 seconds, but this is my conspiracy theory for why there is a hyped up bully character. I think, and this doesn’t work if you do it with Christmas Eve, but I think it’s the exception that proves the rule. I think a lot of these movies, especially as they get worse, like Harley Quinn or Beautiful Mind or Silver Linings Playbook, they put in these really simplistic bully characters to stand in for years and years or maybe even decades of accumulated kind of ableist trauma stems or all of these side comments that people made over the years that you could kind of take generously or maybe they didn’t mean it like that kind of thing. And over time, that starts to become its own kind of subra within you as to how people are being seen you. So if you take that as, or the bully as a stand-in for all of those collective years of trauma that you accumulate from these little microaggressions or maybe major aggressions both, it is a really silly way of representing all of that in one shitty character that takes up way less script time, way less film time to get the same kind of trauma across.

But if you don’t understand how all of those microaggressions can pile up into one big bully, I think that nuance is lost on you. And I think in this case, I don’t know if I would give the hallmark screenwriter credit for that’s what he was doing, but I think it could have been, I think I might come out for an at bat for him trying to represent trauma in a quick and dirty fashion.

Jeff:

Yeah. I struggle with this a lot because to have no bullies would be to imply that there isn’t, that people are all treated great all the time and that we never bring up disability, which is not obviously accurate to say when people get bullied just like anybody else, obviously.

sarah:

Absolutely.

Jeff:

So I don’t think it’s an answer of we should never do this, but I also though struggle with it often feels like there’s this quiet appeal in these characters that the viewer is to learn this lesson, to learn the lesson, to number one, to not be that person. So don’t be the bully, which is probably a good lesson. But then I worry that even more so there’s this story being told around the need to defend disabled people, that the world is hostile toward them and that your job as a strong able-bodied person is to stand up for the weaker in able disabled character who’s going to fall prey to this. Correct.

sarah:

And cannot, cannot possibly defend themselves.

Jeff:

Yeah. Trevor never,

sarah:

Even in the film, Trevor didn’t defend himself. It was his daughter that came out of defense of him, which I think he may have been, that would’ve been an honor fight at that point. But I think even more so there’s a kind of irony to that argument because the film itself, as in the screenplay, spends a ton of time bullying Trevor through all the seeing tons and how he’s walking down the street and he always looks a bit doe-ish and the constant visual similes for blindness and ignorance. The film itself is bullying him in the absolute, and we’re supposed to look at that bully and be like, and that’s why we can never be ableist and it doesn’t work. It rings hollow because the writers themselves are clearly wildly ableist about how blindness operates in society.

Jeff:

Yeah, absolutely. Absolutely. And it’s also that same, how many times have we seen the story that the way to fix a bully is to help a bully? And I’ve always found this really complexing to me. If I think back to my time in elementary school, I genuinely do not think that if I had helped the people that were bullying me, I do not think they would’ve stopped bullying me because that’s not how bullying works. It’s not like a social credit system where, well, I will pay you $10 and now you’ll stop bullying me. It doesn’t work like that because at the root of it, there’s a power thing going on here, but there’s also a whole internal thing going on here with the individual. And so then what I’m watching this scene, and he, number one, she basically PTSD shames this boy who’s wetted his bed even though he’s much too old to wet his bed, which is pretty obviously, I would say aside that he probably has experienced in things in his life. So she bullies an older guy, and I wonder the type of dude who’s going to pantomime blindness to mock a girl whose father is blind. I don’t think that he is going to react with thanks to her intervention. I feel like

sarah:

I learned my lesson. Yeah.

Jeff:

I feel like he’s going to be, the worst thing that could happen to him is that he’s being saved by the person that he is ridiculing constantly. I don’t think that’s how you overturn that power dynamic. So it seems like such a weird liberal dream that, well, if we just help each other, we can all build forms of community and that’s the high road. Which isn’t to say that you should also slam cupcakes in people’s faces either. I also don’t think that that’s how you resolve bullying, but

sarah:

I feel like we can almost picture the writer’s room conversation, and I think you hit the nail on the head with calling it liberal fantasy writing where they’re in the room and they go, okay, how do we humanize this bully to show that problems are relative and everybody has their own shit they’re going through and somebody calls out, what if we give him some very obvious trauma symptoms like late stage bedwetting. So now you’re introducing this whole subplot that you can choose to take interest in who is abusing this 12 or 15-year-old boy and why isn’t anyone reporting this? So instead you just get the daughter like, Hey man, that’s really not cool, and I’m going to mock your trauma coping systems because you make really shitty blind jokes in the lunchroom, and if you take it at face value, sure. You get the relativism argument of even people who are mean have their own shit going on.

And it’s possible that everybody is suffering in many of the same ways you are, even if you’re not visibly disabled. But now you’re introducing kind of layers of trauma and deity or long-term illness through this bully character that the movie doesn’t have a hope of framing correctly. They can’t even frame simpler disorders correctly. So this bully character becomes really problematic in a film theory sense because you don’t get his story rectified. Nobody attempts to actually help him because they’ve already deemed him an antagonist character and we get no resolution as to what happens to him. So it’s disappointing.

Jeff:

We’re almost supposed to laugh at the big bully who pees the bed, who also I guess could be defined as disabled, like leafy body disabled anyways by unable to control bodily function. So it’s like, ha, that guy suffered a trauma. Let’s laugh and mock him. But also we are not to be mocking the blind character that is off limits.

sarah:

Correct.

Jeff:

Yeah. Now we’re such an interesting example, unintentionally I think of the way that disabled population, the disabled community is segmented off from itself. And so you have people talking about, well, we need to do better by blind people in this movie. And then they’re like, but also we’re going to just throw under the bus this other type of disability that somebody’s experiencing.

sarah:

Well, it kind of reflects the ongoing conversation even within CDS of disclosed and undisclosed disabilities because disclosed are the ones, if I’m being incredibly reductive, getting all the love right now, everybody wants to include the disclosed disabilities, the more obvious ones, the ones where there’s no moral argument that they did it to themselves or et cetera. Not as willing to include people with terminal illness, mental illness, kind of long-term, undisclosed disabilities or disabilities, we can’t quite as readily understand as blindness. And that can maybe be typified through the bully character who has some obvious traumas and isn’t accepted the same way as the guy with the easily recognizable, easy to diagnose relatively unthreatening disclosed disability.

Jeff:

Yeah, definitely. Now the last trope that I want to talk about comes to us toward the end of the film. So this is after sort of the major breakdown. Trevor is having this masculine identity crisis. He doesn’t think he’s a real man, he doesn’t think he’s a real professor. And we get this very bizarro scene in which Trevor goes and stands behind the lectern and asks Peyton if he looks like a professor. And he discloses that ever since he became blind, he does not think that people will see him as a professor anymore. Again, seeing him as a professor and that he will not look like a professor. Unfortunately, he does have an app that will tell him the color of his suit, but the app, if he puts it on himself,

Will not say professor, unfortunately. And this also ultimately culminates at the end of the film in which Peyton goes and gives an impassioned speech, which convinces Trevor that despite his disability, he is a real man and he is a real professor, and this is sort of what he overcomes his insecurities and will take back his job and will create presumably a mass murderer in his daughter as he starts to make out with Peyton in front of her. So we have this trope often in film in which it is the role of the non-disabled character to come in and to convince the disabled character that they’re not that disabled after all. That may be the only disability and life as a bad attitude. And this movie leaned into it heavily.

sarah:

So I have continuing my completely unrealistic film analysis of this piece of shit film. I think there’s a really interesting connection here, and you can take it in multiple directions, especially if you’re a better scholar than me between, and I’m doing this on the spot, so correct me if I’m wrong, masculine hyper ability. So him at the lectern being this amazing prodigal totally deserving professor character who can do no wrong, all the tropes that we established with cis white male academics who historically have been put up on these Greek like pedestals with the rampant academic notion that we just cannot seem to erase. And it actually goes back to what we were saying about the film bullying him itself, all of that, his narrative of masculine hyper ability and how he doesn’t believe that he could do that. Well, blind relies on the audience presumption that you thought until this moment that blindness equals ignorance.

Like you entered the film this way and nothing we have done so far persuades you otherwise. So then the end of the film when what’s her face, Peyton is correcting him. Like, no, I think that more people than just cis white males could succeed in the academy. And it’s possible that academics don’t just look like that he does really even seem to believe it. Then it’s a really stilted kind of, oh, well, maybe agreement that speaks more to the masculine ability narrative continuing to ring true, and he can be able, despite his disability. And the word despite is coming from this ignorance narrative that you assume everyone in the room has, which anyone in Disability Gang would be immediately offended by. Why are you taking it as a given that that’s what I think that’s my five seconds of film theory about the end of that film.

Jeff:

No. So you’ve totally tapped into something that I really have wanted to talk about with this film. Yeah. Because to add another log onto the Beautiful fire, or maybe it’s a fire that you’ve built here. Excellent. Is that the movie also? It absolutely draws your eyes to the fact that his blindness is a recent development. The implication being he was not blind when he became this hyper-masculine failure of strength and knowledge that the blindness came after, and that it is now a threat to

His current standing, despite the fact that we do get a scene of him listening to, I believe it was a Christmas Carol and might’ve been, or was it one of Dick Dick’s novel? He’s listening to an audio book of a Dickens novel while he’s holding the book, and they ask him, why are you holding the book? You’re listening to it. And he is like, oh, how it feels. Okay, chill out, bro. Anyways, oh, and so anyway, it’s interesting that the movie is both trying to say, of course you’re still a professor even though you’re blind. But the movie itself had to backfill this story and say, oh, but he was a prophet before he became blind. So he did it before disability hit.

sarah:

Yeah. So you’re saying it kind of negates the narrative that he could have even become a professor if he wasn’t blind or if he was blind, he wouldn’t have made it.

Jeff:

Who knows? Maybe it’s like, did they need to put that in there because they felt that the audience wouldn’t believe it, that a blind man could be this professor? So they had to add that in, and I don’t know which is worse. Did they need it to be this lost narrative? He lost his wife, he lost his sight. They were allegedly not connected, but that he’s experienced these tremendous losses that Peyton and to a lesser extent, max, the dog will now fill that there’s this void that needs to be filled. And one of those voids is his relationship with his daughter, which is strange since the end of the marriage. And the other void is his masculinity. He’s lost his masculinity because he lost his wife and he lost his sight. He’s been castrated and that only a woman being reeded to his life. Can he regain that? And once he’s regained it, what does he get back his job? He’s now allowed to be a pro again because the students and the girl have come together, and now he’s a whole man again, even though he’s still has flaws,

sarah:

Count on Jeff to do a psychoanalytic reading of literally any film he has given.

Jeff:

I’m just saying maybe the walking stick is a penis.

sarah:

Do you thank Deleuze and Guattari directly for that, or does that go in the work cited?

Jeff:

I think that was a Lacan. I think that was more of a Lacanian take.

sarah:

Yeah, I think that’s sort of a Lacan. Well shut out, Jacques Lacan.

Jeff:

I think that Lahan hated this film because,

sarah:

Well, according to your reading, he would’ve loved it.

Jeff:

I’m not saying he wouldn’t have been titillated by it. Oh yeah. I just don’t think he would’ve liked it.

sarah:

Jacques Lacan on masculine hyper ability seen through the body.

Jeff:

Yes,

Mvll Crimes:

Exactly.

Jeff:

So as always, invalid culture is of course a completely rigorous and scientific endeavor, and we have developed a completely scientific way of measuring the quality of films. It is of course our invalid culture rating scale.

sarah:

Correct.

Jeff:

We are going to go through our questions here and see where this film lands on the invalid culture scale. As always, we are playing by golf rules, which means the lower the score the better. So let’s get this started. On a scale of one to five, with five being the least, how accurate does this film portray disability?

sarah:

Are we talking about just whether or not the protagonist was accurately blind one? Yeah.

Jeff:

Did it do a good job of presenting blindness or was it way out in the stratosphere about what blindness is?

sarah:

Well, I think you said the actor was actually blind. Right. So what…

Jeff:

Actor was, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they did a good job of it.

sarah:

No, I think the film was actively mocking him, but in terms of the portrayal of the protagonist being blind, I have to give that a one.

Jeff:

Yeah. I am going to give this a 2.5 is my view on it. I understand that he was fairly new to his blindness, but it also just felt really odd to me that he didn’t seem to understand how to be blind, nor was he actually actively trying to find ways to be blind. I found it odd that all of the solutions to his problems were externally generated, but also he was never animating the finding of solutions. He was always just kind of standing there being like, wow, I’m just going to have to keep running into posts. The beginning of the movie starts with him giving this sort of human rights rant about the legal code against the construction site and being like, there’s not obstructional ball. And you’re like, oh, okay. He’s like an advocate, but then routinely throughout the movie, he just gets completely blown over by everybody and everything, and so I’m like, I don’t know. Yeah, he’s new to it, but that felt a little bit, yeah. So I’m going to revise it. I’m going to give it a two, two out of five.

sarah:

Yeah, I feel you. I think that’s a good consideration to keep in mind.

Jeff:

On a scale of one to five, with five being the hardest, how hard was it to get through this film?

sarah:

Oh, wow. Four. The pacing kills this. This could have been a short film, like 25, 30 minutes, and you would’ve lost nothing.

Jeff:

Yeah, I gave this a five. I feel like this was one of the harder ones to get through. It had both so much and so little like all at once. There were lots of little side plots, the bully side plot, the construction side plot, that learning how to train a guide dog side plot, whether or not he would have a dog. His divorce, the Chad side plot, there was so much going on, but yet it also felt like nothing happened in this film. And that’s, I think never a good sign.

sarah:

What if it was the Banality of Day-to-Day life and how we choose to invest or divest in different parts of ourselves, and he went full hundred percent investment in Peyton and Blindness at the expense of literally everything.

Jeff:

His job. That’s actually why they let him go. Had nothing to do with the construction. They were just like, he is obsessed with his dog trainer. We think there’s a lawsuit coming. We have to get this guy off campus.

sarah:

You haven’t been to work in a week. That’s why we’re letting you go. It’s not the blind thing, and he walks away. It was definitely the blind thing.

Jeff:

Definitely the blind thing. On a scale of one to five, with five being the maximum, how often did you laugh at things that were not intended to be funny?

sarah:

Not as much as Christmas Evil, unfortunately. I would say 2.5. There were some funny moments, but a lot of it was just so dull.

Jeff:

Yeah, I would say I gave this a three. There were a few times where I was chuckling. I mean, I was laughing a lot at just the sheer volume of Christmas. I understand that this is Hallmark, and this is their method. Every scene will be the vomit of Christmas. But there is something legitimately hilarious about seeing a professor’s office in a university in America that is covered in Christmas. Trees is funny. That is funny. And also the dean or chair had literal wrapped gifts on his table. Love that. Literally, what a flex. Bring

sarah:

Back the spirit of Christmas.

Jeff:

Yeah, love it. So I leave it a three, but I agree with you largely this was not as entertaining as I would’ve enjoyed.

sarah:

Amen.

Jeff:

So then last but certainly not least, on a scale of one to five, with five being the most, how many steps back has this film put Disabled people?

sarah:

I think in terms of disclosed disability or disabilities that you can see and readily apprehend and interact with and are fairly obvious to the casual viewer, it does a pretty okay job with OSHA violations and some standard troubles that come with heart of sight. I think in retrospect, only because of the conversation we had today, this film really does undisclosed disability dirty. So for every point that I can award it for being super woke to an extent about some of the hardships of blindness, it felt like it was being reported to me by a 12-year-old girl who had recently read the A ODA, which I’m not saying there’s a problem with, but if the screenplay writer is above the age of 12 years old, I am expecting a little bit more depth. Right. You said golf score.

Jeff:

Yeah. High is bad. One is good. That’s a lot of steps back.

sarah:

That’s a lot. That’s quite a few steps back.

Jeff:

Quite a few steps back. I was more generous on this film. I gave it a two in the sense that I think, as you said, I don’t think they did a ton of harm per se. There was nothing that really sort of stood out. I do take rock off, I think for this repetitive masculine disability wrap up, this insistence that if you’re male and disabled, that you inevitably are going to have these weird hangups about your power proficiency, sexuality, whatever. But I also don’t think that that’s the most egregious of sins, so I’m going to give it a 2.5.

sarah:

It felt kind of tokenism plus not just blindness, but male blindness and what your hangups are going to be as a result.

Jeff:

Yes. Okay, so tabulated our scores together

sarah:

With

Jeff:

The score of 24. My Christmas guide are: Regrets, I have a few.

sarah:

That’s like the second tier, right? That’s not bad.

Jeff:

That’s pretty good.

sarah:

You know what? Not bad.

Jeff:

It didn’t blow it Hallmark. Congratulations.

sarah:

Not on this one. Anyway,

Jeff:

It’s not art. And perhaps because it was so shallow it couldn’t do more harm.

sarah:

That’s true. Yeah. If the dialogue had a little more depth to it, it might’ve actually done more overall damage.

Jeff:

And this concludes another episode of Invalid Culture. Thank you for joining us. I hope you enjoyed it or not. Do you have a film you would like for us to cover on the pod, or even better? Do you want to be a victim on invalid culture? Head to word to our website, invalid culture.com and submit. We would love to hear from you. That’s it for this episode. Catch you next month and until then, stay invalid.

Mvll Crimes [musical interlude]:

I’m arguing with strangers on the Internet // Everyone is wrong. I just haven’t told them yet.